The Substance (2024)

Some films become special to you for one reason or another, or maybe you idealize them to the point you can’t bring yourself to write about them. Then there are films that pursue you, haunting your days and nights, refusing to leave you alone until you finally commit your thoughts to paper. Since the day I first watched The Substance on May 20, I’ve found myself caught in a pendulum between these two states. After my fourth viewing last night, I think it’s finally time to put down my thoughts.

“No exceptions. The perfect balance. What could go wrong?”

Coralie Fargeat’s wildly entertaining and ruthlessly satirical Cannes sensation flips toxic beauty culture on its head with a “be careful what you wish for” fable that promises to resonate for ages.

Elizabeth, unable to accept that the star of her icon has finally dimmed after years of dedication, faces an irreversible reality that compels her to try the impossible — to regain her “better version” through a dangerous formula known as “The Essence.” She achieves her aim, but when things spiral out of control, her “better version,” Sue, takes over. Or maybe control has been lost altogether.

You’ve just read two introductory sentences from the film’s press kit. Yet, these phrases alone no longer suffice to capture the essence of The Substance. Since its early screenings for cinema professionals at Cannes in May, the film has journeyed from the “industry audience universe” into the broader festival circuit and has now reached its widest audience through cinemas and streaming platforms. With each step of this journey, the film has evolved into a different entity — first as a sensational and eye-catching spectacle and now as a piece occupying a space between arthouse and commercial cinema. As someone who has followed every step of this journey, analyzing the film through conventional methods has become impossible for me. Thus, it seems only appropriate to view the film through the lens of Umberto Eco, distinguishing it according to the intentions of the author (the director), the text (the screenplay), and the reader (the audience).

Intentio Auctoris (The Author’s / Director’s Intent)

The following is extracted from the Director’s Statement section of the film’s press kit. The review continues under the section titled The Text’s Intent.

Women’s bodies.

The Substance is a film about women’s bodies.

It’s about how women’s bodies are scrutinized, fantasized about, and criticized. It’s about how, as women, we are forced to believe that we need to be perfect/sexy/smiling/slim/young/beautiful to be valued in society. And about how impossible it is to escape this belief, no matter how educated, strong-willed, or independent we are…

For over 2,000 years, women’s bodies have been molded and controlled by the desires of those watching. Everything around us — in ads, movies, magazines, and store displays — displays imagined versions of us: always beautiful. And slim. And young. And sexy. The “ideal woman” version that we’re supposed to believe brings love, success, happiness.

Everything around us — in ads, movies, magazines, and store displays — displays imagined versions of us: always beautiful. And slim. And young. And sexy. The “ideal woman” version that we’re supposed to believe brings love, success, happiness. And if we step outside these molds — whether with age, weight, or curves — society tells us: You’re done. We don’t want to see you anymore. We don’t want you on our screens. We don’t want you on our magazine covers. We don’t deem you worthy of society’s time and attention. With social media, this situation has become even worse for younger generations…

And I strongly believe this is our prison. A prison that society has built around us and that has become a massive instrument of control and domination. A prison we think we want to be in. And this film says: It’s time to blow this situation up. Because how can this nonsense still continue in 2024?!

I don’t know a single woman who hasn’t had a problematic relationship with her body, who hasn’t had an eating disorder at some point in her life, or who hasn’t felt an intense hatred for her body and herself because she doesn’t look the way society tells her she should.

As I approached forty, I started to feel deeply depressed because I thought, “This is it. My life is over. I will no longer be able to please anyone, I won’t be valuable, loved, noticed, or interesting…” I had studied political science; I was a feminist… And still. This nonsense had found a way to seep into my mind. I genuinely believed that after a certain age, I wouldn’t amount to anything, that I would have no value. Similarly, when I was younger, I believed that if I didn’t have a slim and flawless body, I would have no worth. Crazy, isn’t it?

That’s why I decided to write this film. To confront this issue. And to deliver a political message to the world: We should be done with this nonsense. Genre films are political. For me, as a filmmaker, confronting political and personal issues through the lens of entertainment, pleasure, and excess is a wonderful approach. By going all out, I want to unleash the monster within me. Or, more precisely, the thing that society has led me to believe is a monster: this flawed/aging/changing part of me that I was taught to hide, because as a “woman,” I’m not supposed to look/act/think that way. And today, I’m here to tell you this story.

Intentio Operis (The Text’s / Script’s / Film’s Intent)

As essential as it is to write without altering the director’s intent, it’s equally important that the text’s intent is objective and reflects the director’s vision. Consequently, this section will focus on what the film aims to accomplish, largely based on the press kit — the primary source of the text — and, of course, the film itself.

“Provocative, twisted, and ready to explode! Are you prepared to take down Hollywood? With its own weapon… Coralie Fargeat’s wildly acclaimed Cannes sensation The Substance is undoubtedly among the best of the year.”

It’s evident that the film’s core issue is Hollywood’s nearly century-long history of portraying women’s bodies as objects to be gazed at, desired, and idealized. And this issue isn’t unique to Hollywood. Though feminist theorist Laura Mulvey and art critic John Berger focused on the subject in the 1970s, the notion of women as the objects of male gazes dates back to the earliest examples in film history. Ferdinand Zecca’s 1902 short film Par le trou de serrure / What Happened to the Inquisitive Janitor introduced the term “keyhole effect” to film history, depicting a hotel worker spying through keyholes, especially at women. Likewise, one of cinema’s earliest directors, and arguably the first female director, Alice Guy-Blaché, imagined a world in her 1906 short Les Resultats de Feminisme / The Results of Feminism where gender roles were reversed: women held power and authority, while men were trapped in roles traditionally attributed to women.

Yet, there’s a specific reason why Fargeat’s battle in Substance directs its arrows at Hollywood as well as its feminist outlook. In the simplest terms, the creation of the superstar concept in the 1920s wasn’t just a Hollywood industry initiative or a marketing strategy; it also introduced these ready-made images and public perceptions into society. This evolution of the “star system” transformed fame into something that could be consciously manufactured by the masters of these new ‘glory machines.’ In a male-dominated society, the inevitable result of this display was that women became objects marketed as “objects of desire” on screen, disregarding the psychological toll on the women icons who were unwittingly idolized. By the 1930s, in a world dominated by urbanization, consumer culture, and war, women were cast not only as objects of pleasure but also as seductive femme fatales, seen as threats to family and nation. At this point, women became figures of disorder, cast as temptresses who could ensnare the ‘heroic’ men risking their lives in war. This is the same gaze that made Rita Hayworth the “Devil’s Daughter” in Gilda. Marlene Dietrich became a feminist icon by challenging this gaze and, for doing so, was effectively exiled from Hollywood. To avoid overwhelming this discussion with feminist theory, we’ll stop here to focus on the key points Fargeat addresses.

To fully digest The Substance and understand its primary issues, it’s helpful to examine it alongside films that address the rise and fall of poisoned female superstars under the icon of Hollywood: Sunset Blvd. and Mulholland Dr. Equally beneficial is an exploration of Reality+, Fargeat’s first short film, which uses the sci-fi genre to delve into issues of obsession with desirability and one’s “best version.” Her feature debut, Revenge, confronts the sexual objectification of women and the roles society imposes on them, framing its revenge narrative as a depiction of women reclaiming their stories. The concerns of The Substance are neither new in Hollywood nor in Fargeat’s short career, but she modernizes these issues and takes them a step further.

Now, we come to why the film so heavily employs gore and grotesque elements, horror, and even body horror. First and foremost, as a female director with a feminist perspective, Fargeat is aware of just how traumatic and destructive this issue is. The reality of women who dreamt of being on stage since childhood, only to find that the moment they shine on screen is the beginning of a poisoned youth spent conforming to societal demands, enduring abuse, mistreatment, and exploitation caused by the side effects of this poison, points to a profound wound. Furthermore, being ruthlessly discarded from the very screens to which they dedicated the best years of their lives, witnessing the decline of their once-bright stars into obscurity, serves as a harsh slap that jolts them from their dreams. Norma Desmond losing her sanity in Sunset Blvd. and Diane Selwyn’s descent into madness in Mulholland Dr. are results of the same process. By taking this narrative beyond drama into the horror genre, Fargeat not only reveals her innovative approach but also secures the Best Screenplay award at Cannes with this unique vision and eclectic style.

Technically, the film (in contrast to the superficiality of the narrative) is very strong. There is hardly a need to mention how extraordinary the acting performances are. The chosen frames, camera placement, and angles, as well as the use of sound and music, perfectly reflect the film’s universe. Rather than portraying the character’s psychology in a subtle or deeply emotional way, Fargeat opts to depict it through camera movements, sound, and visual effects. Admittedly, while these highly stylized choices result in a challenging experience, they also attempt to immerse the audience and create a sense of identification with the character, albeit in a somewhat simplified manner.

We mentioned that the film strikes back at Hollywood using its own weapon. By this, we mean not only that the film’s themes are clearly articulated but also that the repetition of actions by the director — intensifying each time — reinforces the message, delivering it to the audience as a full-course meal, complete with appetizers and main dishes. Thus, it is this very approach, in moments where the film veers farthest from arthouse, that allows it to reach the widest audience possible. Instead of dismissing these in-your-face scenes as merely commercial or gratuitous, one should recognize and commend the film’s achievement in bringing its message to the masses. (The impact of the film experience on different audience types will be examined shortly.) Nonetheless, the film’s technical shortcomings shouldn’t be overlooked. Stretching the narrative over 2 hours and 20 minutes inevitably desensitizes the audience and distances them from the core message. Moreover, the disruption of the causal narrative, along with time and logic inconsistencies in the story (tolerable when focused on the film’s main message), leads to criticism labeling it as a careless mainstream movie. In an alternate universe, if the film’s technique had been used more intelligently (and we believe Fargeat has this potential), the story could have been shorter, free of logical errors, more concise, and delivered its message with greater depth on multiple layers. This would have brought it closer to arthouse cinema. Yet, as we’ve discussed, Fargeat isn’t interested in creating another drama film.

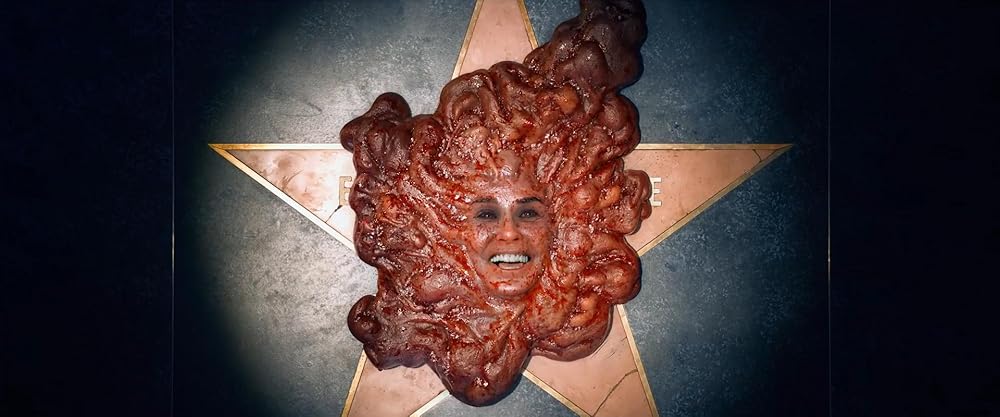

In the climactic scene, the film violently and bloodily takes revenge on Hollywood, idealized bodies, and the male gaze through Monstro Elisasue, as if spilling blood in retaliation for the millions of women worn out and destroyed — because that’s exactly what they deserve, not a bit less, maybe even more.

Another aspect is the references to other films in The Substance. (This section will be briefly summarized, as it has already been widely discussed.) It’s evident that Coralie Fargeat pays homage to iconic horror films and some directors, expressing deep admiration and respect. However, as mentioned earlier, only the Lynch and Cronenberg references genuinely support the film’s themes: Lynch’s countless nods to his mysterious yet unsettling universe and Cronenberg’s body horror and sci-fi elements. On the other hand, the Kubrick and Hitchcock references seem purely pastiche. In our view, these references are more about grabbing attention and reflect Fargeat’s playful personality. (A confession: as a cinephile, whether they are pastiche or homage, I found great pleasure in these references every time I watched the film. Perhaps that was one of the director’s aims.)

Intentio Lectoris (The Reader’s / Audience’s Intent)

Earlier, we mentioned the film’s journey: from industry professionals at Cannes to festival audiences, and finally to the broader general public through cinema releases or streaming platforms. We also emphasized how Fargeat’s film, straddling arthouse and commercial cinema, has managed to reach a wide audience. As such, the film is inevitably interpreted differently by diverse audience groups, sometimes even in two extremes, based on their expectations and personal interpretive tendencies.

What’s crucial to note here is that, regardless of whether the audience likes the film or not, the most accurate reference comes from the ‘exemplary reader/viewer’ who can engage in a dialectical relationship with the director or the film’s intent. Thus, for a film reaching a broad audience, interpretations that stray too far from the text or the director’s intention and are excessively subjective should be disregarded.

Additionally, a harsh reality is that the film has been commodified and fetishized as a PR object (such as Sue/Elizabeth’s costumes and other items from the film being sold). This consumption without proper understanding of the film’s essence has cheapened the experience for cinephiles or conscious viewers, directly opposing the film’s original intent.

In conclusion, despite its flaws, The Substance demonstrates Fargeat’s significant potential as a young director. Her future projects will undoubtedly play a defining role in her cinematic career. If Fargeat can distance herself from commercial concerns and fully embrace her creative vision, the film world will gain a masterful director.

Nil Birinci