Mulholland Dr. (2001)

In this analysis of Mulholland Drive, we delve into the intricate layers of Lynch’s surreal narrative, where the boundaries between reality and dream blur into an indistinguishable haze. The film explores themes of identity, guilt, and the subconscious, using symbols like the blue and red transitions, the Club Silencio scene, and the fragmented nature of Diane’s psyche to reflect the human condition. Through a lens shaped by Lynch’s Buddhist influences and his masterful use of psychological horror, we uncover a story of personal breakdown, self-delusion, and an inevitable confrontation with the self. As Diane navigates the labyrinth of her mind, we too are invited to confront the mirrors within ourselves, leading to an unsettling yet profound understanding of the elusive nature of truth and the silence that follows.

Let’s start by talking a bit about the project’s story – Mulholland Dr actually began as a television series. ABC gave the project the green light and requested a pilot episode. Lynch went and shot a 125-minute pilot episode, which defied typical TV series themes and structures, being different and slow-paced. The network executives found it too strange and asked Lynch to cut it down to 37 minutes and re-edit it to be more “TV-appropriate.” Lynch reluctantly cut it to 88 minutes, but due to the removed scenes, the series lost its coherence. Consequently, ABC decided to shelve the project.

Meanwhile, in 1999, Lynch attended the Cannes Film Festival, where he received an offer from his French producers to turn the TV project into a film. Studio Canal offered additional financing, which allowed Mulholland Dr to be realized as a feature film.

Now, let’s look at the Lynchian – or Lynch-esque – characteristics we’ll see in Mulholland Dr: Lynch has a unique style of storytelling, built on his distinct foundations. We’re in a world balanced on the border between light and dark, between sleeping and waking. This world is filled with mysteries and discoveries, hopes and fears, and dreams – it’s both terrifying and wondrous. Many scenes that seem like dreams aren’t exactly dreams; they are worlds formed by human perception, where reality is shaped by how we understand it.

In Lynch’s cinematic language, human existence is absurd. People feel the anguish of being, shape their lives through momentary decisions, and sometimes fail to the point of tragic endings. In Mulholland Dr, we’re performing an autopsy of Hollywood with Lynch, but it’s an autopsy that disregards the rules. Here’s what that means: With Lynch, we dismantle Hollywood’s narrative-plot-reality format. At the same time, we break the pressure of linear storytelling, focusing on the reality of life. Narrative exists in the details – in objects, close-ups, and the performances that create reality.

We break the linear narrative because, as Lynch sees it, life doesn’t progress in an ordinary flow. The film is like a Mobius strip in a Lynchian sense. The audience is not forced to solve the intentions behind changes in time.

Another unique feature here is that, in mystery films, we’re usually kept guessing, left wanting to know the end. But Lynch gives viewers hints about the end and clues throughout the film and expects us to create our own versions of the story over this mystery – which goes far beyond what he imagined; as many viewers as there are, there are stories, as many endings as there are viewers.

The film is a deepening reflection of Hollywood’s allure, performance, and self-discovery. It’s as if we’re within a psychological depth that only the frame can contain, watching a conflict between the ideal self and the real self. At the beginning of the film, we have a knot to untangle; the more we try to solve it, the more it tightens. Here, we turn to Kubrick: “The most important parts of the film are the mysterious parts that the mind and language can’t reach.” So do these parts and details emerge from the whole or lead to the whole?

The first scene opens with a jitterbug dance sequence. This can be seen as a tribute to Cab Calloway’s 1934 song “Call the Jitter Bug.” Jitterbug dancing became popular in the 1950s, which also serves as an early homage to the 50s, a decade Lynch holds dear. It’s worth noting that jitterbug is a partner dance, which may foreshadow Betty’s duality.

The dance performance, created through overlapping images and doubling effects, produces a kaleidoscopic impact.

From the shining image of Betty Elms as a dance star receiving applause, we transition through red bedspreads into another world—a dream world where desires are fulfilled. The blurry vision and palpable tension of someone struggling to breathe are presented side by side.

After taking a breath, the scene clears up, and we realize we’re seeing things from her perspective while she’s lying in bed.

Then, as the dream or fantasy begins, the scene darkens. Alongside Betty, our sense of reality also fractures. Through that fracture, we fall freely into the dream world.

At this point, we should take a moment to examine the function of dreams (Colin Odell – Michelle Le Blanc – David Lynch):

Dreams actually reveal the unconscious desires and fears of the dreamer.

However bizarre or exaggerated they may be, dreams originate from everyday life.

Lynch is someone who makes the unconscious visible. He not only reflects the hazy, half-remembered state of dreams we wake up from but also focuses on the absurdity of the world.

In Lynch’s cinema, emotions and feelings govern logic and thought, nourishing dreams.

Dreams don’t just reflect our world; they expand it, and in some cases, they invade it. Lynch’s world exists on the boundary between the absurd and the logical, where the surreal encroaches on the concrete.

As Wittgenstein said, “To seek the world beyond the world, perception and the beyond, dream and reality.”

Everyone and everything we see in the dream is actually a part of ourselves, reflections of fragments of our being. Each archetype in our dream is a permanent inhabitant of our dream space or fantasy world, caretakers in the house of our being.

The following scene begins with a shot of the Mulholland Dr. sign. Mulholland Dr. is a poorly lit road winding along the peak of the Santa Monica Mountains, nestled among the wealthiest and most privileged residences of Los Angeles. Mulholland Dr. is almost like a representation of Hollywood’s shadowed, twisted pathways, its hidden and dark depths. At the end of the road on the map lies the famous Hollywood sign. We see the city’s enchanting lights from above. We know Lynch loves to play tricks on his audience; he even gave this film the tagline “A love story in the city of dreams” But we know that Mulholland Dr. actually speaks to these themes:

Hollywood’s fake paradise,

the dreams it promises,

and the underlying truths.

Yes, it criticizes the system, but beyond that, it drifts through power games and shattered dreams. This film is Hollywood’s look at Hollywood, and, most importantly, it’s a tribute to all of Hollywood’s fallen angels. Mulholland Dr. is the road to Hollywood; you race to reach it. You need to overtake the rival car on your right without tumbling off the narrow bends. If you’re fast, you take the risk of death and push the gas pedal. But if you slow down, you lose – you end up a forgotten, failed actor in a rundown house.

Through a POV camera, we see Los Angeles through Rita’s eyes. Though it seems captivating, it’s a city that perhaps carries the traces of millions of shattered dreams within its cells. Baudrillard says, “Los Angeles belongs to the hyperreal; it’s an unreal evidence drawing energy from the real.”

Here is the famous Club Silencio scene, summary of the film. The design of Club also pays homage to Edward Hopper’s Two on the Aisle. (For other art references in the film, see: https://kinoavantgarde.com/mulholland-dr-filminde-sanat-referanslari/)

If we combine Lynch’s perspective with Club Silencio, we see that we, as people of the 21st century, live in a postmodern world of representations. Life itself has become immersed in cinema, music, and visual art, turning these into our reality. Our lifelong struggle is to control these representations, that fake reality, while simultaneously standing against the world and our own lives—our own reality—like a successful actor or director controlling the representation. The self, representation, and controller of representation are split into two, just like Rita and Betty.

No hay banda – this is not a pipe. Silencio raises the audience’s awareness, showcasing the traits of postmodern cinema: in this scene, we see and hear everything we’re not supposed to in a theater/performance. Moreover, this is all done by the host, who’s expected to cover everything up—everything is fake, there’s no band, everything is prerecorded; from the spotlights, the relativity of reality, to the singer who will soon collapse and be dragged offstage. The offstage spills into the onstage.

The magician symbolizes the devil, revealing the dark side of evil to Diane. We also see the blue-haired woman for the first time here as a harbinger of death, of merging with nothingness. Who is the blue-haired woman?

We transition from red to blue. This shift will lead Diane’s awakening from the fabrications of her fantasy into the harsh realities of life. Looking again at Lynch’s color codes, blue contrasts with the manifestation of red. In this visual world, red represents the emergence of reality, while blue unveils it.

We see that the magician holds all control. He raises his hands, and we hear thunder and see flashes of lightning, and Betty begins to tremble as if she’s lost control. When the magician relaxes his tense arms, his expression softens, and the rumbling ceases, allowing Betty to recover from her spasm. A devilish grin appears on the magician’s face as he folds his arms like a vampire in a coffin. He then vanishes in a cloud of blue smoke, signaling the end of Betty’s dream and foreshadowing her inescapable fate.

We again witness the red and blue transition. Looking more closely at these color codes: in optical science, the movement from a lower energy state to a higher one is called a “blue shift.” Perhaps that’s why Lynch uses the color blue to symbolize the key transitions in Diane’s inner and outer realities. It’s the realm where illusions reign, and thus it’s where the heart of Hollywood lies. From Lynch’s perspective, it could be argued that blue is the essential color of Hollywood’s mystery.

At the start of the film, when Betty leaves the airport, she has a blue suitcase. This suitcase represents Diane’s transition into this surreal fantasy because it, along with the blue smoke and the blue box, symbolizes a container that will later lead her out of her fantasy. As red becomes more prominent, we move into the reality within the dream. The blue box is a memory container filled with painful recollections—a dark memory, Pandora’s box. Even the monster had one. In reality, it’s just a trivial box in the drawer where Diane keeps her gun. At some point, the fantasy world inevitably turns into a nightmare, and the return to reality begins. The character faces her inadequacies and starts to cry in this scene. Rebekah falls unconscious, yet the music continues—emphasizing the artificiality, proving the magician’s words. Another Hollywood jab—though you are moved to tears, nothing is authentic—there’s no band; everything is playback and fake. Another proof of this is not a pipe.

With Betty’s realization of the truth at Silencio, the dream ends. Camilla is no longer in her life, and when she sees the black void inside the blue box, Rita’s presence vanishes. Now, with both Betty and Rita’s personas having returned to Diane, everything she once loved is gone. When hope dies, the dream ends as well.

The scene concludes with Aunt Ruth returning to the house after Betty and Rita are completely gone. When Diane can no longer succeed even in her escapist dream without Camilla and Aunt Ruth, she ends it. The dream ends.

Lynch shows us Aunt Ruth’s house again from her perspective; it’s a dream, and Betty and Camilla never actually went to that house—there’s no trace of their presence, not even the blue box on the carpet.

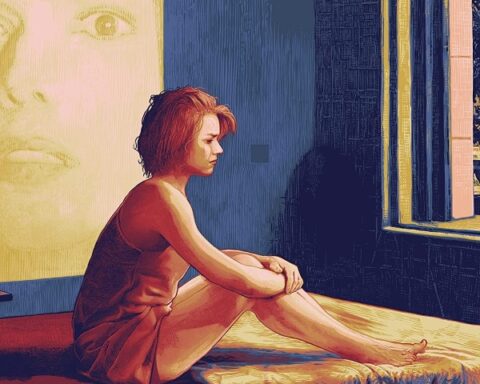

Diane had fallen asleep to cope with her depression. While asleep, she entered an extraordinary fantasy where her mind attempted to process everything that had happened. Unfortunately, her fantasy did not help her cope with her suffering, and she won’t wake up any better off than when she first drifted to sleep.

We see Diane lying in bed, this time alive, wearing the same outfit and in the same position as the decayed corpse in her dream. The corpse never existed in reality—it’s not the real Diane in the final scene who takes her own life; it’s the dreaming Diane. Same nightgown, same bed, same room. In the dream, the corpse has a gun in its hand but no bullet hole in its head. It’s Diane, metaphorically dead from all she has endured, a living corpse.

The transitions between blue and red again blur the line between reality and dream. However, this doesn’t mean we return to the fantasy/dream sequence; rather, it shows that Diane’s mind has become so clouded that she can no longer distinguish between reality and dreams. We also see from her facial expression that her mental stability is deteriorating.

Unfortunately, she cannot escape her problems and find a promised land “somewhere over the rainbow.” Her problems will follow her everywhere (self-reference). This dream reflects how, by watching this film, we too are escaping our own worlds, and when we focus on the film, we become aware of our own escape from reality. This is what Lynch is portraying: we all idealize the dull, dark, and bleak aspects of our lives in our dreams and fantasies. But reality is different, and when life doesn’t give us what we want, we find ourselves in despair.

As Diane is dying, we once again see the face of the monster behind Winkie’s. It is reflected in the mirror because the monster was a part of her, representing a distorted personality that led her to do something she could never forgive herself for.

As Diane is on the brink of death, she sees herself beside Camille with the blonde wig, as though the two characters have merged and found true happiness. As we discussed earlier, Diane’s desperate wish to hold on to two things comes together: her innocent self from the past and the passionate star persona she always wanted to be. By ending her life, she takes a form of revenge against everything she has lived through, because now she is free from guilt and, as she approaches death, she has embraced both the Betty and Rita identities.

Mulholland Dr. is an impressionistic and nightmarish journey into the psyche. The film’s constructed world feels like an explosion from the psychic realm — each minor character in the dream is a reflection of Diane’s fragmented self. However, when the pieces come together, the whole transcends the individual, and the spirit of the world, as well as the individual psyche, are somehow interconnected beyond the limits of the universe. When you get too close, the mirror breaks, and this causes pain. Eventually, the most important truth is realized: there is actually nothing to understand.

We return to Club Silencio. The woman with blue hair tells us to “Silencio,” silencing us. This woman represents Ruth Aunt’s ascended form after her death.

Let’s explore the Silencio scene further. Before going insane or committing suicide, a person enters a phase of complete silence, where communication with oneself is entirely cut off and even sounds cease. This scene symbolizes the moment of psychological breakdown. Considering Lynch’s Buddhist background, looking at Mulholland Dr. with this in mind makes more sense. The Silencio scene marks the beginning of the death process. Like the red room in Twin Peaks, Club Silencio serves as a transitional space, a waiting room — akin to the bardo process where one must wait up to 49 days before passing to the next life. In the first weeks of bardo, a person may not realize they are dead and return to their daily life. However, when they notice that their reflection does not appear in the mirror, or their shadow does not fall, they understand they are dead. The shock of realizing this can cause fainting, which overlaps with Diane’s trembling scene. In bardo, some may become trapped and remain as spirits or ghosts (Rita Aunt – The woman with blue hair). Lastly, bardo is often described as a space bathed in blue light (just like the blue ambiance in Silencio).

THE END

- Wittgenstein ended his Tractatus with the following words: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” Perhaps this is Lynch’s answer to the audience who tries to make sense of the film.

- Dostoyevsky also said, “The only way to survive is to learn the art of silence.”

Best to finish with a passage from Shakespeare’s Hamlet

“Consciousness makes cowards of us all.

The pale light of thought

Clouds the natural color of what comes from the heart.

Who would want to endure all of this,

Groaning and sweating under the weight of a hard life,

If death’s unknown land did not frighten the heart?

To be, or not to be, that is the whole question!

Is it better to endure our thoughts,

The cruel fists and arrows of fate,

Or to face the sea of misfortune,

And say ‘enough’ in silence?

And now, indeed, the rest is silence.”

Nil Birinci