The Lolita in the Mirror

Before bedtime, in the late and dark hours, an old woman would begin to weave her tales with the threads of dreams. As she illuminated her face filled with wrinkles with fire, her eyes were darker than the night itself. She would narrate to the gathered people with a crackling voice, rising and falling. The most attentive listeners were the children nestled in their mothers’ laps, watching her with curious eyes. “It all started,” said the storyteller, “with the story of a little girl with a red hood. With a basket filled with fresh cookies on her arm, she embarked on a journey into the dark forest.” As she spoke of the red-hooded girl shivering at the sound of a twig breaking under the wolf’s paw while walking alone on the path to her grandmother’s cottage on the other side of the forest, the children nestled even closer to their mothers.

Yes, it was discovered thousands of years ago that fiction could narrate reality, sometimes even the truths that couldn’t be spoken. Even today, if you were to stop someone on the street, they could recite from memory the continuation of the tale where the girl reaches the cottage. It’s a narrative that has lived for almost an eternity. But could the truth behind this narrative be very different from what we know? It is said that the red hood of the girl symbolizes the onset of puberty, announced by menstrual blood, and the cookies in her basket symbolize her virginity. The mysterious forest represents her undiscovered sexuality, filled with unknowns like an uncharted forest. Her elderly grandmother is passing her place in the cycle of life to her. Moreover, the red-hooded girl is bewildered and naive. There’s perhaps no need to dwell further on her reactions to the wolf’s oversized organs, such as his ears and nose. Looked at this way, the story of Little Red Riding Hood takes on a deeper meaning, becoming a narrative of a young girl’s transformation into a young woman. This tale, with different versions, has been told in Nordic, Russian, and even African communities. We all grew up with these tales, even if we didn’t know the hidden meanings behind them. The story of Little Red Riding Hood is one of the oldest known templates of the Lolita archetype.

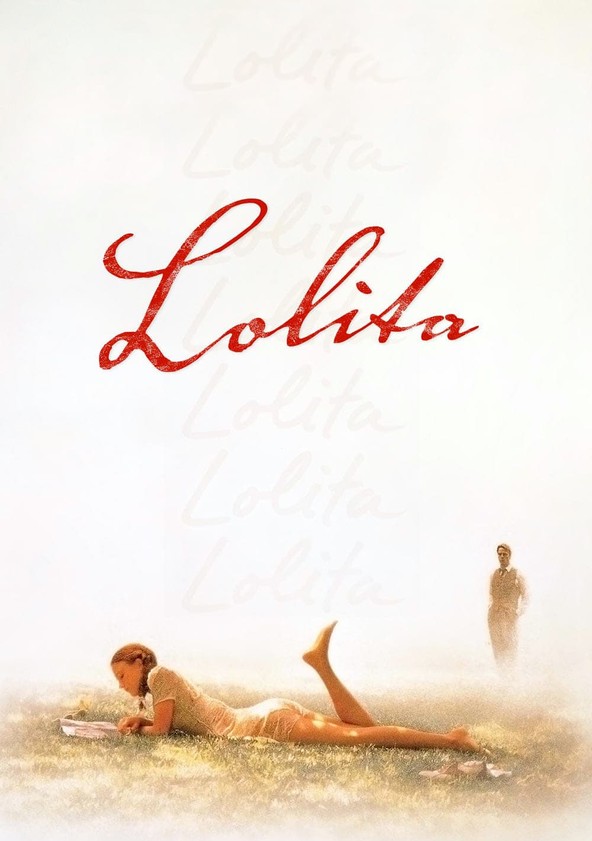

Cinema, inheriting the legacy of storytelling, couldn’t stray far from these tales. The terrifying tales of inexperienced female sexuality would find a name for themselves. Coined after Nabokov’s controversial novel published in 1955, the term “Lolita” entered our lives. Nabokov, fleeing from the oppressive regime in his country to seek refuge in Europe, couldn’t be selective about the publishing houses for his books, as only those producing obscene materials responded to him. His early works were thus published in this manner. The novel Lolita, besides its literary value, caused a stir due to its subject matter when it was first published. Unable to find a publisher in America, it was attempted to be published censored in England. In the bastion of free thought, France, it became the subject of a trial, albeit one that would eventually fail. For those unfamiliar with Nabokov’s Lolita, it can be summarized briefly: The main character of the novel, Humbert, meets Dolores when he is in his forties. Dolores, whose mother has died, is a girl who struggles with the hardships of life on her own. Her innocence and beauty lead Humbert into the clutches of his uncontrollable desires. Humbert names her Lolita. Though Lolita isn’t a weak character, she will find herself in conflict between the expectations constantly imposed upon her and her evolving identity, just to survive. The period covered by the novel continues until Dolores reaches the age of seventeen.

Even before Nabokov, the famous Japanese author Jun’ichirō Tanizaki penned the novel “Naomi” in 1927, which features a girl raised with the goal of marriage by a man. Despite cultural and temporal differences, the portrayal of the girl through the eyes of the narrator bears a striking resemblance to Nabokov’s Lolita. In that book, Naomi, born in a den of iniquity, is a character who struggles with life’s hardships alone. Lastly, if we go back a bit further to 1912, we encounter the short novel “Death in Venice.” In this work, the famous author Thomas Mann tells the story of an old man who falls in love with a young boy. Unlike the others, his is a platonic passion that he never manages to communicate, yet it shares the commonality of desire directed towards innocence and beauty, albeit in a morally controversial context.

It’s worth noting that several of these novels were later adapted into films, notably Luchino Visconti’s “Death in Venice,” among others. It’s important to mention here that for a long time, the storytellers of cinema and literature were predominantly men. However, we can’t overlook those who could portray the essence of femininity most directly and rawly. One of the first examples that comes to mind is the French director Robert Bresson. In his film “Mouchette” (1967), he tells the story of a poor, rural girl who has to endure her father’s torments while taking care of her dying mother and her infant sibling. The dark forest, rainy nights, and desolate hut… When you think about it, there are so many similarities with the story of Little Red Riding Hood. Mouchette, in a way, may seem like Lolita, but we could also say she leans towards the archetype of the saint. Good storytellers have the power to narrate the complexities of human nature in its most straightforward yet nuanced form.

In the end, cinema, inheriting the narrative legacy of fairy tales and mythology, continues to whisper to us the darkest secrets of our nature around its fire. In the shadows cast upon our perceptions of femininity and masculinity by timeless archetypes, we discover the depths of our desires and fears. The archetypes of femme fatale, saint, and wise woman are also shrouded in mystery. Following Lolita, perhaps the next writing could be about the femme fatale archetype. After all, Marlene Dietrich, with her siren-like gaze, calls us to her deadly charm, and how can we resist such an invitation?