Deadly Seductresses

Do you hear the song calling to you from the dark depths? A voice full of longing is calling your name. You know where the path to her leads. A deadly and dangerous end. One step, then another, and a few more steps. There you stand before her. Have you recognized her with her misty gaze, with the inviting smile at the corner of her curled lips? She dances. Wild, beautiful, and agile, she dances while her hair sways, as scorching as fire, distant and untouchable. Your hand, extended in the void, freezes for a moment in the air. Because you know. There is a price to pay for touching her.

From Homer’s sirens to the forest fairies of Northern Europe, from Salome mentioned in the Bible to the deadly seductresses of ancient times like Cleopatra, despite their obvious dangers, we humans offer them our unconditional submission. Perhaps the reason for our inability to resist lies in a desire for annihilation inherent in our existence. What do their incredible legends say about the mysteries of human nature?

This time, let’s start with what they are not saying. What is a Femme Fatale not?

Chronologically, the first confusion arises with Eve and the expulsion from Eden. Was Eve, the first woman in the creation stories of all monotheistic religions, the mother of humanity, a femme fatale? We can say that Eve, who was deceived by the serpent into eating the forbidden fruit in paradise, leading Adam to do the same, was more a harbinger of humanity’s curiosity for knowledge than a malevolent seductress. In a sense, she is a curious part of human nature. She has no malicious intent and feels ashamed of what happened after eating the apple. Furthermore, her fertility cannot be considered a characteristic of a femme fatale. We will explore the relationship between femme fatale and motherhood later; for now, we can say that a mother cannot be a femme fatale.

In discussing the literary reflections of the femme fatale archetype, Virginia Woolf’s “A Room of One’s Own” (1926) is mentioned. While it may not be surprising that independent, curious, and unconventional women are interpreted as malevolent femme fatales, it is open to debate. Similarly, with the onset of modernization, many successful female artists who gained fame in the art world, previously dominated by men, are also considered femme fatales: Colette, Anais Nin, George Sand, Sarah Bernhardt… Were these women considered femme fatales because they were successful, or were they successful because they were interpreted as femme fatales due to their unconventional relationship choices and their power over men? What about characters like Madame Bovary (Gustave Flaubert, 1856), who committed the greatest sin against the sacred institution of marriage with her infidelity, or Anna Karenina (Leo Tolstoy, 1873), who pursued her passions and fell into endless remorse, willing to give up her life? Can they be considered femme fatales?

Despite often being confused due to their disregard for rules, once we have somewhat delineated the boundaries of what the deadly allure archetype is not with these examples, we can move on to what the Femme Fatale is.

The most accurate starting point for this description may be Homer’s sirens. The sirens in Homer’s epic poem “The Odyssey” are famous sea nymphs known for their beauty and enchanting songs. Sailors who follow the sirens’ songs are met with the fate of their ships crashing into rocks. We find similar characters in Nordic legends, such as the forest fairies guarding the northern forests. Another example of allure, beauty, and deadliness is Salome. In the Bible and historical writings from the ancient Roman period, Salome performs a mesmerizing dance at King Herod’s banquet. The king is so impressed by her dance that he grants Salome a wish. Salome asks for the head of John the Baptist. The legend thus arises that Salome, with her allure, causes the tragic death of a prophet.

As we transition from ancient and prehistoric legends to the modern era when printed literature became widespread, we can start with Dostoevsky, one of the pioneers of psychoanalysis, when discussing archetypes. It’s no coincidence that his female characters oscillate between the Virgin and the Deadly Seductress. Characters like Nastasya (The Idiot, 1869) and Grushenka (The Brothers Karamazov, 1880) are portrayed as polar opposites to innocent and virtuous young women, using their sexual allure to manipulate men for their own purposes. Similarly, Zinaida, the impoverished aristocrat in Turgenev’s novella “First Love” (1860), seduces many men to pay off her mother’s debts and ultimately leads the protagonist’s father, who has fallen in love with her innocently, to a tragic end. As we turn to Europe, we can mention August Strindberg’s “Miss Julie” (1889) as another unconventional femme fatale. This play, which had a significant social impact when it was first performed and later adapted into a film with the same title that won the 1951 Cannes Grand Prix, revolves around the captivating Julie, the dazzling daughter of a wealthy family. She seduces Jean, one of the servants, during a midsummer night’s celebration, despite being engaged. Kristin, the cook, who is religious, pure, and hardworking, symbolizes the virtuous and good woman in contrast to the seductive Miss Julie. Considering the emergence of the women’s rights movement in Northern Europe during the late 19th century, we can easily say that the rise of femme fatale characters is not coincidental during this period. The relationship between the two becomes quite interesting at this point. While the femme fatale symbolizes a modern, independent, and liberated woman in narratives, she also attracts criticism from both feminists and their opponents for representing a woman who merely uses her sexuality and allure. Does it matter to the femme fatale that she draws both the ire and hatred of the characters she portrays? We can give the word on this to Rosamund Pike, who was asked about what she thinks about the hatred her characters receive from audiences: “Perhaps there is much to learn from these women who don’t care what is thought about them.”

Jokes aside, while it is impossible to ignore the interaction between feminism and the femme fatale, as well as the fear-hatred relationship that develops towards them, when it comes to archetypes, it would be quite narrow-minded to frame the discussion solely in terms of feminism. To truly understand what we are, why we fear, we need to deepen this context by shedding our preconceptions and biases.

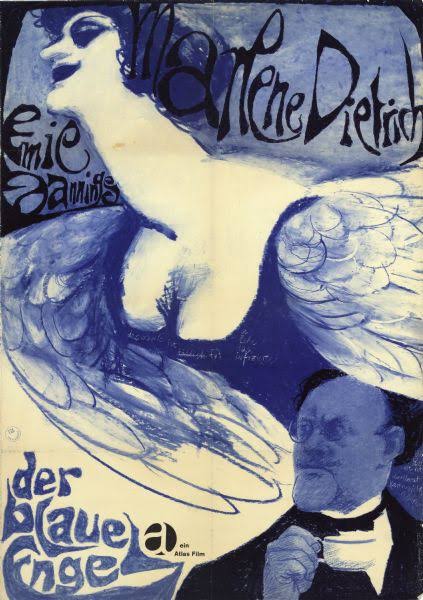

Cinema, like literature, provides an extensive field where we can trace archetypes, and perhaps even more so due to its visual nature. When we mention Femme Fatale, one of the first names that comes to mind is undoubtedly Marlene Dietrich. In pre-World War II Germany, the film that brought her fame, “Der Blaue Engel” (1930), is a narrative of deadly allure from start to finish. The film’s main character, Immanuel Racht, with his name inspired by Immanuel Kant and his ethical stance as a symbol of moral rectitude, begins his story with the motto “Tue rech und scheue niemand” (Do what is right and fear no one). However, before we delve into Professor Immanuel Racht, we can mention the few female characters in the film, such as the emotionless, mechanical servant who serves the professor. This woman, depicted as the antithesis of deadly allure, serves the professor, displaying no emotions, and not comprehending male desires. Viewing through this lens, while Lola reigns as the focal point of desires and beauty in the cabaret, the only female figure presented against her is the servant, characterized as emotionless, mechanical, and ignorant of male desires. In contrast to the professor’s indifference upon finding his dead bird, exclaiming “Yes, there is no longer a noisy bird left,” the scene shifts to Lola, whose room is filled with bird sounds, and who meets every silly move of her admirer with a sweet indulgence. Shameless, unabashedly flaunting her exquisite legs, conscious of her beauty but dangerous nonetheless. Her danger will persist until the professor loses all his respectability, profession, daily routines that give meaning to his life, and his students. Lola never hides who she is. Yet, she does not harbor any sympathy for the men ensnared by her deadly allure. There is a price to pay to reach her, and this is her world, what can she do about it? In the final part of the film, we witness the once-respected professor reduced to a pitiful clown on stage. Although his former colleagues revolt against his downfall, the working-class welcomes his fall with enthusiastic joy. His fall drives them almost mad with delight. Slowly violating all his boundaries, the professor is eventually condemned to complete oblivion. The foolish man once intoxicated with love now understands, though too late, that there is no turning back from the boundaries he crossed for love. On the other hand, Lola continues on stage, now dressed in jet black instead of her previous white attire, continuing to sing her song. Here, in its purest form, Lola embodies the Femme Fatale character on stage.

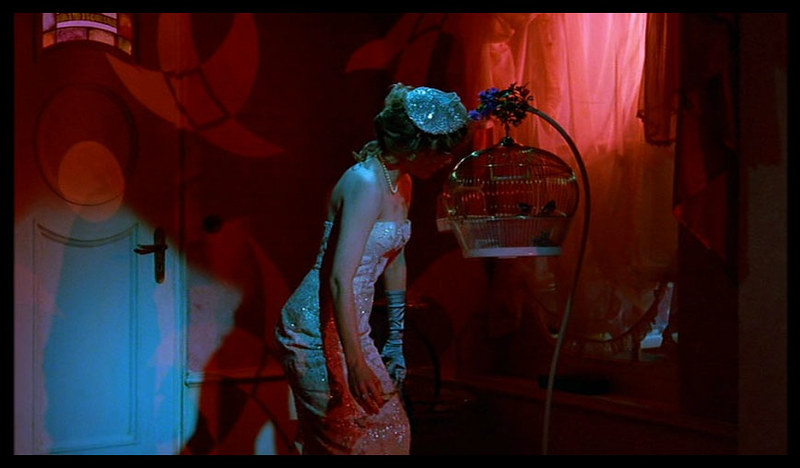

“Der Blaue Engel” not only brings Marlene Dietrich fame that will allow her to portray numerous similar characters until her death, but also serves as inspiration for many directors who followed. One of the most famous among them is Rainer Werner Fassbinder. His film “Lola” (1981), part of the “BRD Trilogy,” is an adaptation of “Der Blaue Engel.” Fassbinder’s passionate love for his country, Germany, finds embodiment in Lola’s miraculous abilities. The magnificent and powerful female characters, sometimes subject to glorious falls, are indispensable figures in Fassbinder’s works. However, Lola’s ending is not as pessimistic as “Der Blaue Engel.” Fassbinder chooses to preserve his hope in Lola’s child, as she is the only femme fatale characterized by motherhood. Motherhood stands in stark contrast to the femme fatale archetype. The wives and children waiting at home for the sailors seduced by the sirens. Perhaps at this point, we should take a moment to look at the dark and light sides of archetypes.

Although an archetype may be dark in nature, the confidence of the Femme Fatale, her disregard for societal norms as she pursues her passions, her ability to live without needing anyone—especially a man, separates her from the traditional role expected of women, empowering her. What she lacks is adaptability and motherhood. If we were to list the attributes expected from an ideal mother, they would be the exact opposite of the Femme Fatale archetype. While we can easily differentiate between the archetypes of the femme fatale and mother, in reality—when it comes to flesh and blood—such a distinction does not exist.

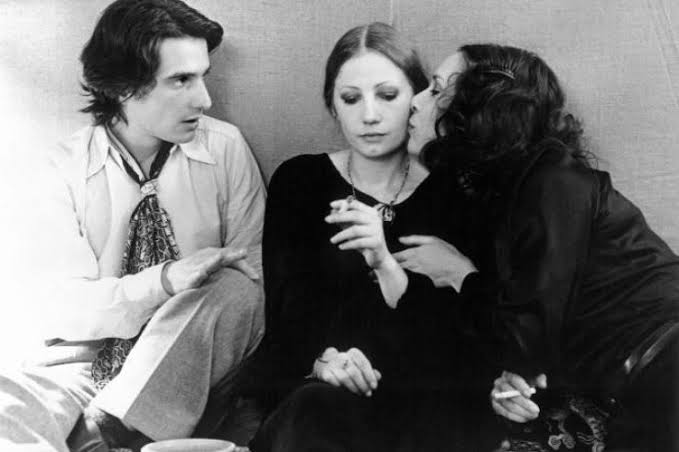

At this point, we can transition to Jean Eustache’s film “La Maman et la Putain” (The Mother and the Whore) (1973). In a time permeated with the sense of emptiness and hopelessness felt by the generation of ’68, the film’s characters struggle with a void that consumes everyone and everything, from gender roles and ethics to individual and societal values. The film’s characters subvert and redefine all norms, and in doing so, they blur the line between themselves and the archetypes of the mother and the femme fatale. “I’m neither a mother nor a whore,” the women declare, or “I’m both a mother and a whore, depending on what you mean.” While the film opens with the protagonist, Alexandre, falling into the web of a femme fatale, his escape marks its end. Alexandre, self-proclaimed as a penniless ordinary young man, begins cohabiting with Marie, the owner of a clothing store. Marie, older than Alexandre, becomes his sole source of income, providing him with shelter, food, and clothing, much like a mother. There are no secrets between them; Alexandre doesn’t hide his flings from Marie, and as long as they stay within certain boundaries, Marie tolerates his dalliances as minor indiscretions. Marie acts as Alexandre’s mother, supporting him financially, sheltering him, providing him with care and emotional support. However, Alexandre encounters Veronika, a young woman who shares his mundane existence. Working as a nurse to support herself, Veronika spends her earnings from night shifts on clubbing. She openly expresses her desire for sex and has no qualms about it. Sexual encounters hold no special meaning for her; her relationships are casual and devoid of significance. Alexandre’s knowledge of Marie’s relationship with him does not deter Veronika’s desire to captivate him. A night spent together in bed with Marie sleeping next to them leads to Alexandre and Veronika’s intimate encounter, followed by Marie’s suicide attempt, further complicating their situation. In a world without boundaries, where love, lust, and desperation intertwine absurdly, Marie becomes Alexandre’s mother, and Veronika becomes his femme fatale. Nonetheless, Veronika’s constant carrying of tampons, removing them before having sex with a man, and her menstrual blood dripping onto the carpets seem to foreshadow her potential for motherhood. In the end, Veronika expresses her desire to become a mother to Alexandre, suggesting that a child could give meaning to their absurd lives. This scene marks the conclusion of the film, leaving Alexandre and Veronika as if a child could bring purpose to their nonsensical existence.

As we transition from old dreams to Hollywood, we see that Hollywood often used the archetype of the femme fatale as a one-dimensional and highly popular formula catering to the masses’ erotic expectations. Films that do not offer anything new artistically but exploit the universal nature of the femme fatale appeal to millions of viewers. Movies like “Fatal Attraction” (1987), “Basic Instinct” (1992), and “The Game” (1997) established Michael Douglas as the recurring victim of femme fatales. In reality, Michael Douglas, who confessed to being a sex addict, embodies the role of a man struggling to escape various troubles caused by his inability to resist the sexual allure of dangerous women. “Basic Instinct” introduces one of the most audacious femme fatale characters, Catherine Tramell (Sharon Stone). Accused of the murder of a man killed with an ice pick during sexual intercourse, Catherine, a famous author, becomes the prime suspect due to her novel depicting a similar murder and her relationship with the victim. Alongside her provocative, daring nature, Catherine’s solitude, wealth, and astonishing intelligence make her one of the femme fatale archetypes of the 20th century. With her captivating allure and the danger she poses, men both desire her passionately and fear her dreadfully.

Turning to the East, we find fewer examples of the Femme Fatale archetype in cinema and literature. In the East, while the image of powerful, feared females akin to the nature and goddesses is not overlooked, interestingly, neither literature nor cinema makes room for Femme Fatale characters. In ancient Chinese texts, there are noblewomen entangled in intrigue, but considering them as examples of deadly allure is somewhat forced. However, in Egypt, we find a more fitting example. Egypt, known for its oriental dancers and the birthplace of Cleopatra, naturally brings us to Shabab Emraa (A Woman’s Youth, Salah Abouseif, 1956). In the film, Tahiyyah Karyuka portrays the character of Shefaat, a middle-aged, wealthy, and lonely woman. When a young man arrives in Cairo for his education, he becomes a tenant in Shefaat’s house. Shefaat, in a romantic relationship with the young man, teaches him many things about life while distancing him from his fiancée, family, and spiritual values. The film begins with the young man falling into the snare of a femme fatale and ends with his escape from her influence. Although the film did not win any awards at the Cannes Film Festival that year, it gained significant attention as a symbol of the Egyptian freedom movement.

In conclusion, the Femme Fatale archetype has been a recurring theme in literature and cinema throughout history, representing a powerful and alluring figure that captivates and terrifies. While evolving in its portrayal, from classic Hollywood to modern cinema, the essence of the archetype remains rooted in its defiance of societal norms, its ability to live without relying on anyone, and its allure that ensnares men, often leading to their downfall. Whether in Western or Eastern narratives, the Femme Fatale continues to fascinate and intrigue audiences, embodying both the dark and light sides of human nature.

When we look at what kind of counterpart Femme Fatale has found in the East before coming to our day, we don’t encounter many examples. In the East, although the feared-powerful image of nature and female goddesses is not without response, it is interesting that neither literature nor cinema makes room for femme fatale characters. In ancient Chinese written texts, there are women from ruling dynasties involved in intrigues, but it would be a bit of a stretch to consider them examples of deadly charm. In this sense, we find the closest example to the archetype in Egypt. It is not surprising that we find ourselves in Egypt, the homeland of oriental dancers at the peak of seductiveness and Cleopatra, as the image of the woman beckoning us at the entrance. In the film “Shabab Emraa (A Woman’s Youth, Salah Abouseif, 1956),” the character Şefaat portrayed by Tahiyyah Karyuka is a middle-aged, lonely, and wealthy woman. A young man who comes to Cairo for his education starts to stay as a tenant in Şefaat’s house. While Şefaat teaches him a lot about life in the emotional relationship he enters with the young man, she will also lead him away from his fiancée, family, and spiritual values. The film starts with the young man falling into the trap of a Femme Fatale’s web and ends with his liberation from her influence. Although the film shown at the Cannes Film Festival that year did not win an award, it made a lot of noise as a symbol of the freedom movements in Egypt.

Skipping the ages when the East and the West diverged and coming to our present day, where all cultures are interconnected with invisible threads and are starting to resemble each other greatly, we see that the pure femme fatale archetype appears before us as multi-layered characters mixed with other archetypes. The character Hicran in the movie “Hayat (Life, Zeki Demirkubuz, 2023)” is one of the examples of deadly charm. Almost emotionless and cold, she bewitches men with a magical charm and leads them to disaster. Her ex-fiancé, who sacrifices his freedom for her, her husband who is on the brink of psychological problems due to jealousy, tries all the ways to reach her. However, Hicran has impenetrable walls. Although she is not happy with the disasters she causes, this does not prevent her from listening to the call of her freedom. Towards the finale, Hicran undergoes a catharsis and transformation. After minutes of crying scenes, she frees herself from the femme fatale character and surrenders to light, love, and ultimately motherhood. A classic encounter of the femme fatale and mother archetypes. Although classic endings are like this, this encounter does not always lead to bright outcomes. At this point, we can give the example of Gracie Atherton (May December, Todd Haynes, 2023), which is quite intriguing because of the malicious combination of the mother and femme fatale archetypes. Gracie, as a married and motherly woman, seduced Joe, a 13-year-old friend of her children, and when their scandalous relationship was revealed, she was sentenced to prison. After getting out of prison, she continues her perfect suburban life by marrying Joe and living in her lakeside home. Almost perfect. From the first scene in the film, it is understood that Joe is trapped in a marriage where he does not know what is right or wrong and has become a puppet under Gracie’s domination. Gracie, who abused Joe, imprisoned him in her marriage and her life full of personal imbalances even when he became an adult. From this perspective, Gracie has become both the mother and the deadly seductress of Joe. Ignoring societal norms, Gracie, who drags everyone’s life into tragedy for her desires, leaves the audience face to face with countless questions as one of the complex and malicious characters of the intertwined circle as both a femme fatale and a mother.

To break the recurring mother-femme fatale cycle a bit, we end it with the movie “The Power of the Dog (2021),” where the seductive character is not a woman. In Jane Campion’s film, a male character possesses the deadly charm, and what’s more interesting is that he uses his killing charm for his mother. This could be the most revolutionary interpretation of the femme fatale and mother cycle after Jean Eustache. Moving on to the plot of the film; Phil and George Burbank are two brothers in a poisonous relationship. George marries Rose to break out of this cycle, but Phil, perhaps because of his character or perhaps because of the pain of losing his beloved in the past, does not allow love to blossom in the house. He targets Rose at every opportunity, dragging her into the quagmire of psychological problems and alcoholism. At this point, the arrival of Rose’s son Peter – our deadly charm – will shatter them. Although he seems weak and naive, Peter, who makes Phil fall in love with him with calculated and devilish steps, turns him into his slave. Peter’s ability to use his charm as a weapon and to commit murder without the slightest hesitation for his mother’s salvation makes him a unique deadly seducer.

From legends to modern cinema, even if it changes its form and gender, the Femme Fatale will undoubtedly continue to exist as an archetype that will always confront us. Although its complex nature, blended with other archetypes, sometimes makes it difficult for us to recognize it, when we hear its song from the depths and feel the irresistible invitation behind its hazy gaze, we will know that it is her. Although we may fear her and often become angry while watching her, we now know that what we fear the most and what angers us the most show us the places where our strongest desires and deepest secrets are hidden.

Zeynep Bakanoglu