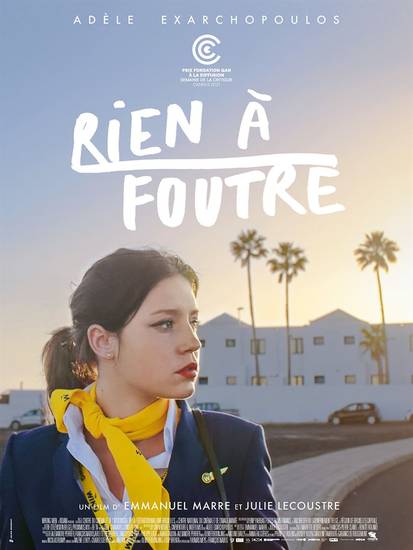

Zero Fucks Given

The film, shot in four countries in 2020 and premiered at the 74th Cannes Film Festival, is presented on Mubi under the Millennial Meltdown category, but it would be unfair to limit it to that category. The portrayal of a young woman’s grief after losing her mother intentionally starts off superficially, but as the film progresses, it delves into a timeless depth.

Why does it start superficially on purpose? The reason can be linked to the film’s origin. The first idea for the film came from the expression on a flight attendant’s face that Marre and Lecoustre noticed during a flight. When they saw a thoughtful, introspective expression on her face, instead of the superficial, smiling mask she was supposed to wear while hundreds of passengers watched her, they became curious; wondering what she was going through at that moment, where she would go once the plane landed, and what kind of life she had. This journey, which they deepened from a superficial image, turns into an inner journey that also extends into the life of the film’s main character, Cassandra. At this point, I must add that Adèle Exarchopoulos’ significance for the film goes beyond just playing the lead role. The directors talk about how in their mix of reality and fiction, they let Adèle express her inner world with her “thousand-faced” acting, and how they crafted the film by simply conversing with her, without directing her, as they proceeded with improvisation. (*) This was the exact formula that brought the film its success.

The film is also technically quite accomplished. Shot in segments and skillfully edited, the film features documentary-like sections (with music reminiscent of 1980s documentary scores), as well as shots showing the characters from 360 degrees. While this collage of various techniques might seem good on paper, it also holds a risk of disrupting the film’s natural flow. Zero Fucks Given applies it successfully that it doesn’t break the immersion. The directors, who took a significant risk accomplished a difficult task. Although I’m not opposed to speed in cinema, it’s true that if pacing is not properly adjusted – just like in music – it can lead to disaster. While some might find the slow pacing too slow, I personally think it adds depth to the film, reminiscent of real life. Breathing spaces are provided, allowing us to absorb the subtle moments that capture our attention and to empathize with Cassandra’s feelings.

What are these subtleties? One such scene is when Cassandra slowly walks on the moving walkway at the airport, with the phrase ‘Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die’ displayed on a giant billboard behind her. In the fast-flowing river that people throw themselves into to escape and forget, Cassandra is too fast for life, but too young to die as a woman still in the bloom of youth. She has lost so much ambition in life that she doesn’t even bother correcting the chief steward who fails to address her by name or pursue her promotion. Instead, she chooses to show her life on social media under the nickname “Carpediem.” Seize the day, forget yourself. One wonders if she chose this nickname before or after losing her mother. There’s enough time in the film to contemplate this. In another scene, a tense phone call with a woman we later learn is her sister suggests that she’s trying to escape her family home. This feeling is left to simmer, without much explanation, like a nagging toothache. Later, when we see her at the family home, it becomes clear that what she’s trying to escape isn’t the house, but life itself—the life she doesn’t know how to continue, one that’s become an autopilot blur, much like the mix of documentary and fiction in the film. It’s a fog of being lost, where the road back to reality can’t be found. This feeling isn’t restricted to modern times or the modern individual, although the mediums where people choose to lose themselves may have modernized, the emotions are as old as humanity itself.

At this point, we can conclude with Emmanuel Marre himself, where he beautifully summarizes the film’s emotion, speaking about loss, getting lost, and coming back:

‘Anyone who’s been through a very difficult experience or depressive states can imagine this: you’re on a train platform. Trains pass by, people get on and off. You’re on the platform, but you just can’t get on. You constantly wonder, “What does it mean to come back?” Maybe it’s not a return, but rather the question is, “Can what was lost be found again?” and “In what condition?” The only journey is that of someone who learns not to abandon anymore, but learns to leave. There’s a huge difference between abandoning something, fleeing, and leaving something. That’s the journey.'”