We continue our deep dive into Mulholland Dr., a film of which analysis and artistic references we’ve previously explored. This piece serves as a complementary addition to our earlier review, focusing on two main areas:

- Film References – Sunset Blvd., Le Mépris, The Wizard of Oz, Inland Empire, and Gilda

- Betty & Camilla and Others – The Dream World and Shifting Identities

1. Film References – Sunset Blvd., Le Mépris, Inland Empire, Gilda, and The Wizard of Oz

Sunset Blvd. (1950) Around the ninth minute of the film, we see the Sunset Blvd. sign, marking the first of many references in the film. In essence, both Sunset Blvd. and Mulholland Dr. serve as reflections that critique the decline of Hollywood’s identity and that of the actress persona. This is one of Lynch’s many nods to his admiration for the 1950s.

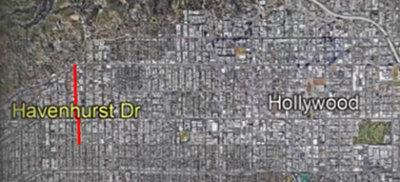

Winkie’s! In the film, Winkie’s restaurant is located on Sunset Blvd., symbolizing the avenue of broken dreams.

Betty’s destination, Aunt Ruth’s house at 1612 Havenhurst on Sunset Blvd. (thus on the path to Hollywood), also references Norma Desmond’s home. We will also see many similarities inside the house.

Coco’s Kangaroo is a nod to Norma Desmond’s monkey. Inside, they find a wallet filled with cash, symbolizing how Hollywood takes what it wants from Camilla, erasing her memory and identity and replacing it with money. They even contemplate killing her, paralleling Norma Desmond (another Sunset Blvd. reference).

Ann Miller and Lee Grant (Coco and Louise), being former Hollywood actresses, serve as Lynch’s tribute to the 1950s. In the Silencio scene, Rebekah collapses unconscious, yet the music continues—a critique of the artificiality of Hollywood’s emotional impact. The moment the truth gains momentum in silence is actually Silencio. This is another Sunset Blvd. reference—having lost the human voice in the 21st-century production chain, only playback remains; nobody cares when a woman collapses from exhaustion.

Le Mépris (1963) ve Godard

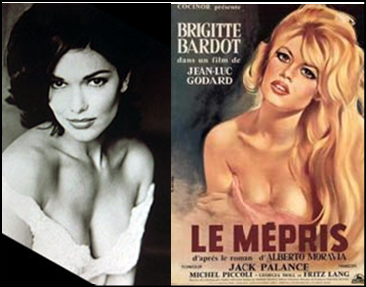

ita takes her name from Gilda, but who is Camilla in real life? Here we turn to Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mépris (Contempt). Our main character, Camille, played by Brigitte Bardot, wears a dark wig and gazes at herself in the mirror. Her red robe is a slightly darker shade than Bardot’s post-shower robe in Le Mépris. Both characters unite over expectations of the seductive female image. The multilingual magician in Silencio speaks several languages (Spanish, English, French), a nod to the three languages used in Le Mépris.

Camilla’s appearance at Adam’s house is also a Camille reference; Bardot strikes a similar pose in Le Mépris. In addition, Camille in Le Mépris quotes a book about Fritz Lang: “Crimes of passion are useless. I love a woman, she betrays me, I kill her. What remains? I’ve lost the woman I loved because she’s dead. If I kill her lover, she’ll hate me and I’ll lose her again. Killing is never a solution.”

Camilla’s appearance at Adam’s house is also a Camille reference; Bardot strikes a similar pose in Le Mépris. In addition, Camille in Le Mépris quotes a book about Fritz Lang: “Crimes of passion are useless. I love a woman, she betrays me, I kill her. What remains? I’ve lost the woman I loved because she’s dead. If I kill her lover, she’ll hate me and I’ll lose her again. Killing is never a solution.”

The blue-haired woman is, in fact, Aunt Ruth’s spirit rising after her death. Here’s the evidence: 1) Aunt Ruth appears as Betty’s dream ends; as soon as the film ends, the blue-haired woman appears. 2) Rita once says, “Your aunt has beautiful red hair,” and in the dream, this color turns blue. 3) At the end of the film, she hushes us with “Silencio,” accompanying Diane’s eternal silence—her death—ending the film, much like Le Mépris.

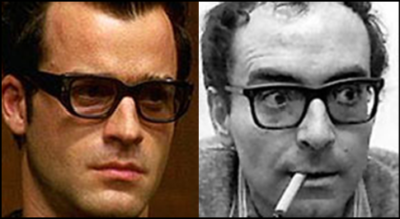

And who does Director Adam resemble? None other than Jean-Luc Godard.

Inland Empire (2006) and the “Woman in Trouble” Theme

After the accident at the beginning of the film, Rita descends without knowing who she is. Here, Lynch’s recurring motif of the “woman in trouble” is apparent (in Mulholland Dr., later echoed in Inland Empire thematically). So, is it Rita who’s in trouble, or someone else?

Betty is a small-town girl determined to become a Hollywood star. She arrives in La La Land in a pink, gleaming sweater representing an almost childish innocence. Note the color shifts: after four dark scenes, Hollywood greets us with a bright, artificial, and smooth facade. Every age of woman is represented here. In this film, both main characters are in trouble, one in reality, the other in a dream. Perhaps not just actors, but also women who arrive with purpose but fail to achieve success are vulnerable here; no woman is safe in Hollywood, at least until she rises to a certain level.

Adam’s phone scene resembles a cut from Inland Empire. A dim room with gloomy, cracked, and peeling walls represents a metaphor for descending into the soul through a crack in the hotel room wall. Adam must decide and act.

The backyard imagery in Silencio will recur in Inland Empire, signifying the eerie essence of the location.

Laura Dern & Naomi Watts

Gilda (1946)

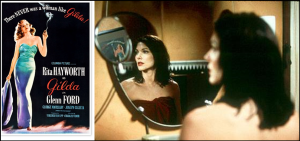

Rita has no real connection to Aunt Ruth. This fabricated relationship aligns with the fake associations created by adopting the glamorous name Rita Hayworth. In Gilda (1946), Hayworth plays a mysterious character who captivates men with her femininity and allure. Rita’s true character in Hollywood mirrors this. Hayworth herself married five producers, changing her physical appearance with each relationship and paying the price of fame—making her name choice especially meaningful here.

The Spanish origin of Rebekah in Silencio alludes to Rita Hayworth. Born to a Spanish father and Irish-American mother, Rita arrived in Hollywood with heavy makeup concealing her ethnic identity, much like Rita.

The Wizard of Oz (1939)

Let’s briefly explore the references to The Wizard of Oz: the themes of sexual ambiguity, a young girl’s journey, and the American narrative come together here. Lynch’s affection for Oz is evident in many of his films. For example, in Wild at Heart, the character Dorothy clicks her heels, and there are scenes with a good witch. Lynch used Oz as a loose screenplay template when writing Mulholland Dr. Essentially, in both films, a young girl whose wishes remain unfulfilled finds escape in dreams, where she distorts real-life people and events, only to return to reality in the end.

The real-life Winkies restaurant was originally named Caesar’s, with the draft script referring to it as Benny’s. However, Lynch changed the name to allude to The Wizard of Oz.

The Wicked Witch of the East’s broom is hanging on the dirty wall in the backyard of Winkies restaurant.

In the final scene, the protagonist, unfortunately, does not find a promised land “beyond the rainbow” to escape her troubles; instead, they will continue to follow her.

Other Homage Examples

The camera perspective uses a technique similar to that in Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad, showing two faces merging into one. This technique has also been used in Agnès Varda’s La Pointe Courte (1955), Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966), and Woody Allen’s Love and Death (1975).:

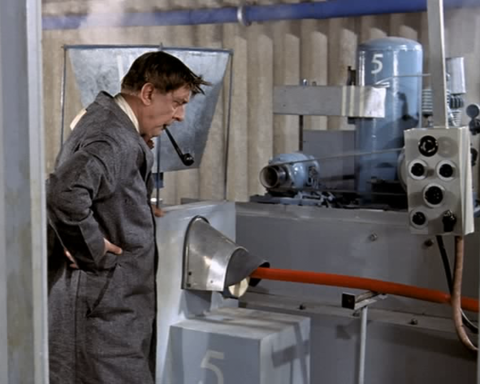

The man in the background with a red pipe is a nod to Jacques Tati’s Mon Oncle. Lynch incorporates this pipe into other films like Wild at Heart and Blue Velvet.

Mon Oncle & Wild at Heart

2. Betty & Camilla and Others – Dreams and Shifting Identities

The first people Rita encounters after the accident, who could offer her help, are drunks. This indicates that only Betty can truly save her. Betty wants Rita to depend on her.

The car accident on Mulholland Drive represents the “short-circuiting” of Betty’s mind in real life. She feels that she faced numerous threatening figures that night, hence the accident becomes a transformed element in her dream. (Lynch could have titled the film Mulholland Drive, but he left it as Mulholland Dr., which introduces a dual meaning—Mulholland Drive/Dream). As Lynch indicates, something happened to Diane Selwyn on Mulholland Drive. It’s not Rita’s ordeal but Betty’s. In a key dialogue: “D: It’s strange to look for yourself. R: Maybe I’m not who you think I am.”—Lynch’s hint about identity.

If we examine the color coding in Betty and Rita’s first clothed encounter, Betty is in pink, symbolizing innocence, while Rita is in red, representing sensuality. The contrast even extends to their nail polish—clear versus bright red. We see Betty as the small-town schoolgirl and Rita as the femme fatale. Rita compliments Aunt Ruth’s red hair to make a good impression on Betty. This is crucial because we’ll see later how Aunt Ruth’s red hair left a strong impression on young Betty, who loved her aunt dearly. This connection allows Diane’s innocent Betty persona to link her affection for her aunt with her feelings for Rita in her dream.

Betty covers Rita with a robe left by her aunt. While the robe is clearly intended for Betty, it’s laid over Rita, symbolizing Betty’s inability to earn the rank or status to wear it herself.

“C’mon, it will be just like in the movies—we’ll pretend to be someone else.” This is a pivotal line because Lynch offers here the film’s core clue about its nature: everyone in the dream is pretending to be someone else. In the dream, Betty helps Rita, while in reality, Camilla assists Diane. The main focus here is Diane’s identity crisis.

Betty’s talents don’t help her alone; in her dream, it appears that Adam was forced by a mafia-like group to choose Camilla, reflecting the idea of Camilla as “The Girl”—whether she charmed Adam to get the role or was chosen by force. Immediately afterward, Betty withdraws, moving away from the person who ousted her (Camilla), saying, “I need to be somewhere else” and turns toward Rita, who in her dream depends on her.

“I remember something.” Psychogenic fugue—a short-term memory and identity disorder where memory shifts elsewhere and later returns. It’s a theme also explored in Lost Highway.

In the final moments of scene 21, a doubling effect occurs, and Rita transforms into Betty. Since the onset of separation anxiety, each repressed desire activates an unconscious matrix of fear and longing, resulting in a fragmented psyche through trauma. The concept of “being whole” actually begins with a split identity as soon as primary drives are suppressed. Returning to real life, what we’ve seen up to this scene was initially designed as the plot for ABC’s show. What follows is Lynch’s breakaway, showcasing his unfettered vision with no constraints—now the film becomes gorier, sexier, darker, and more violent.

Betty is in love with Rita, much like David Lynch, as he often mentions, is enamored with his ideas. In this context, Rita represents Betty’s ideal self. On duality—Rita embodies Betty’s ideal self, and by merging with her, they achieve a form of unity. According to Lynch, the women in his films represent different facets of a single psyche, collectively reflecting the unconscious mind through his lens. These women are also, symbolically, expressions of Lynch’s anima, his inner feminine aspect.

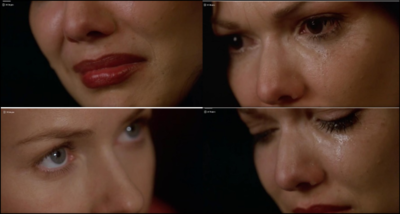

There is a brilliant four-shot montage reminiscent of Eisenstein, where Rita and Betty communicate through glances:

- (Lips) – “I can’t tell you what I did.”

- (Tear) – “What I did made me cry.”

- (Betty’s eyes) – “I know; I’ve seen it.”

- (Rita’s downward glance) – “I’m sorry.” Through Rita’s face, Betty essentially forces a confession, acknowledging she paid to have her killed—a kind of veiled absolution.

In the “real” universe of the film, we visit Adam’s house, where Camilla meets Betty and says, “Shortcut, a beautiful, secret path.” This suggests that since Betty couldn’t rise to the top on her own, Diane succumbs to becoming a casting couch actress, with “shortcut” symbolizing this Hollywood seduction. Camilla, in this sense, embodies Hollywood’s allure—Hollywood equals Camilla. Also worth noting is that Camilla is wearing the dress she wore in the car crash scene from the dream.

In Adam’s house, Coco repeats her line from the dream but now as Adam’s mother, not his manager. The fluid identities of the dream world are entirely reshuffled. Sartre’s “Hell is other people” resonates here as Betty’s dream reconstructs people according to how she wishes to remember them. We see everyone’s real selves at the dinner (with Adam being the only character unchanged from beginning to end). Coco, eating walnuts, has her close-up—a stunning association with memory and recollection. Coco’s last name, La Noix (walnut), mirrors this theme.

The only character who appears in the real world but not the dream is Adam’s associate, Wilkins, who reminds Diane of truths she doesn’t want to hear at dinner. In the dream, his dog soils the garden where Coco is the manager, signifying that Diane—like many of us—refuses to see the messiness of reality.

Betty the waitress (named Diane in the dream) is kind despite spilling her coffee cup, mirroring Diane’s deep-seated longing to reclaim her innocent self. Before coming to Hollywood, Diane was similarly innocent, and a part of her hopes to escape her suicidal tendencies through this purity and forgiveness, a kind of self-defense.

Badalamenti

Composer Angelo Badalamenti, Lynch’s partner and friend, underscores Lynch’s descent into depth and darkness. The haunting, evocative score deeply shapes our viewing experience, supporting the mood of the visuals while also carving its own path. Critics have called Mulholland Dr.’s soundtrack Badalamenti’s “darkest, most melancholic, and mysterious work” to date.

Lynch famously asked cinemas to play the film “3 decibels hotter” to enhance the auditory experience.

Mr. Roque, Castigliani Brothers, Cowboy, and Hollywood’s Mob Men

In one scene, Mr. Roque is in a luxurious hotel lobby, on the phone saying, “The girl is still missing.” This reflects Diane’s fantasy of Hollywood raising a commotion about her while she waits in her apartment. In Diane’s mind, Mr. Roque symbolizes some form of power in filmmaking, and Diane’s Rita character forms a connection with him—a powerful little man with substantial backing. He, like the Castigliani brothers, agents, Cowboy, and those who control Adam’s film, represent the power brokers of Hollywood.

The thick-necked characters’ faces are never fully revealed. We see the back of one man’s neck as he speaks offscreen and the arm of another man, yet none of them have a complete, unified identity. They’re like fragments that can’t come together. This also hints at some of the underhanded conspiracies in Hollywood; the shady dealings in dark alleys have become trivial, carried out by nameless intermediaries.

When we reach Adam’s meeting with the producer, the distorted, high-angle shots combined with the city’s tense Badalamenti music create a threatening atmosphere, as if swallowing everything within. In all his splendor, we see Badalamenti as Luigi Castigliane, who later appears as the man staring at Betty at dinner. With his grand attire and car, it’s clear he is a power player in Hollywood.

The director’s assistant, caught in between, observes the situation with serious awareness. He gives a speech to soften the atmosphere and prepare Adam. The director and crew, who demand only the “best” coffee, must seek perfection to appease the producer, yet he’s never satisfied, even with the best.

The powerful figures in suits, especially the Castiglianes with their black/gray suits and red ties, also exert pressure on the director and assistant through their behavior and attitude.

The dismissive, arrogant, and highly oppressive producers intensify Lynch’s anger and resentment toward the Hollywood dream. The mafia-like structures dominating the film industry reveal themselves here, too. Diane attributes her failure to get good roles to this mafia-like system; she was a phenomenal actor with a flawless performance, fully deserving of the role.

Adam’s golf club becomes a phallic symbol as the least authoritative person in a room filled with powerful men, which also critiques the film production industry. Remember, “MD” didn’t get approved by ABC because it didn’t fit the format they wanted. Lynch explicitly highlights this in this scene.

“Is that all, sir?” is another Lynchian critique of the producer’s endless and ultimately absurd demands. The whole room tries to please the producer, but even the best effort falls short. Luigi Castigliane, as a frighteningly perfect Italian, drinks only a perfect espresso.

The limo-smashing scene represents Adam’s challenge to Hollywood’s dark forces, a moment of striking back with his smaller phallic object against the larger one. But, of course, he won’t go unpunished. Diane projects part of herself here as well. Notably, in 1994, Jack Nicholson smashed a car with a golf club in the same spot (albeit for different reasons).

Let’s turn to Freud. In the meeting between the director and producer, we have four groups: the id (the Italian brothers), the ego (Adam, the director), the superego (third group), and Mr. Roque, whom we’ll meet later, representing wholeness of self. The id is aggressive, acting solely on desires — harboring lust for Camilla. The superego is innocent, moral, glancing at Camilla as a beautiful girl and making only objective comments. Watch how they conflict. The director, as ego, tries to find a middle ground but lashes out unnecessarily, attacking the car (the id). He opposes the id’s desires.

After the meeting with Ryan, the third group (superego) speaks with Mr. Roque (the decision-maker, symbolizing self-integrity). The first thing we notice is that the third group representative, Ray, has to speak to Mr. Roque from behind a glass wall with a speaker. Mr. Roque sits in a wheelchair, remaining in the dark until Ray begins speaking. Mr. Roque has an assistant beside him, but neither moves or speaks much.

We’re actually witnessing a conversation between Diane’s superego (moral side) and her wholeness of self. The superego says to the self, “If you want everything shut down, we’ll shut it down,” implying that to maintain her integrity, she makes the decision to kill Rita, even if she regrets it later. This Freudian reading also acts as the ego-repairing part of Diane’s fractured personality, sensing her freedom’s violation, and locking her rebellious, deviant side (Roque) in the basement.

Remember, all these characters are archetypes of Betty, and archetypes are guardians of the soul. This connects us to Jung. As a dark force seated in a locked wheelchair behind thick glass, opening into the hidden basement of consciousness, Mr. Roque is the animus of Lynch’s consciousness. This seemingly insignificant figure sends agents and provocateurs into the business world. We also saw this figure and scene in Twin Peaks. The figure is inspired by Francis Bacon’s Seated Figure, an artwork reflecting the artist’s intense, distorted portrayal of the human form, depicting inner turmoil and emotional tension with hues of red, brown, and darkness. Bacon’s focus on deformation and movement highlights the fragility of human existence; this approach reflects his interest in existential anxiety and decay. Enough said about Lynch, I think.

Sonny Boy Williamson’s “Bring it On Home” plays. The Castiglianes take a bit of revenge at Adam’s home. Danger continues to haunt Adam. In her dream, Diane belittles Adam, making him a small puppet in her hands, which adds a humorous absurdity to these scenes by Lynch.

Scene 15 starts with dark images of Hollywood. The hotel owner implies that Adam has hit rock bottom and can’t fall any further, so he needs to make a decision.

The meeting place with Cowboy is under the Hollywood sign; Cowboy is the symbol of success in Hollywood. He calls Adam to the top of Hollywood because, in Hollywood, everything advances from the top — Lynch’s critique of Hollywood’s hierarchy.

Think back to Lost Highway — the recurring image of yellow road lines signals an unsettling path. We see Adam on his way to meet the Cowboy.

Anti-Edisonism — there’s a theory that you can’t control electricity in dreams, which reminds us that we’re in a dream. As the Cowboy enters, he lights up the space, like a star entering the stage. The electricity, light, and scene are entirely under his control. The strange Cowboy, who also appears in Wild at Heart, symbolizes Golden Age Hollywood in this film — Hollywood’s thoughts, expectations, arrogance, and hidden games.

This is, in fact, a message to the audience. Instead of saying, “I’m watching the film,” Lynch says, “Don’t be a smart aleck; sit and think.”

ynch continues speaking to the audience. “I’m driving the cart, meaning I’m directing the film, but if you succeed, you’ll join me in the seat, and we’ll direct the film together.” We already know Lynch likes involving the audience in his films.

Lynch continues his critique of the film industry. The producers wanted to change Mulholland Dr., even saying they wouldn’t approve it unless their conditions were met. Lynch reflects this in the film. We see Cowboy two more times, but Adam never sees Lynch’s game with the audience. As Cowboy leaves, he takes away the electricity/light; the scene and the show are over.

Cowboy ile birlikte, Lynch’in “freak” karakterlerinden birkaçını kısaca konuşalım – Mulholland Dr.‘da hangi “freak”leri gördük? Tekerlekli sandalyedeki adam, parmak boyutundaki yaşlı çift, kasıtsız cowboy. Bu meta-estetik dokunuşlar, aynı zamanda Lynch’in ressam ve video sanatçısı olarak yer aldığı sanatsal geçmişinden tanıdık ikonlardır ve birçok filminde karşımıza çıkar. Peki Lynch neden bunları ekler?

- Lynch, surrealist bir ressamdır; bu tür karakterleri filmlerine yansıtması da onun doğal bir eğilimidir.

- Suistimal veya faydalanma asla değildir, aksine bunlar, insanlığın çeşitliliğini bir açılım olarak, paletini zenginleştiren unsurlardır.

- Lynch aynı zamanda bir Zen Budisti’dir – insanların nasıl göründüğünden bağımsız olarak, herkesin içinde hem iyi hem de kötü vardır – Yin Yang öğretisini hatırlayalım.

- Lynch, bir bilinçaltı gerçekleştirenidir. Bu tür varlıklar kabul edelim ki, hepimizin bilinçaltında varlar.

The Monster and Dan

Dan is somewhat naive, and in reality, he is the only potential witness to a possible murder. He may have grasped the situation, and this understanding might have seeped into his dream. Since Adam is rather innocent, this revelation may have come to him. Notice also the similarity in names: Dan/Diane, suggesting Dan might be one of Diane’s personas. (He’s the one who’s doing it) – Diane’s personality would, of course, protect her by casting the blame on the “monster.” When Dan looks at Herb, he experiences a kind of déjà vu, as Herb is standing exactly as he does in Dan’s dream. Realizing that his nightmare is turning into reality terrifies Dan. Could Herb’s presence be the result of Dan’s narrated story? Do our dreams create and shape reality, or is reality shaping dreams? As Freud suggested, are dreams merely fleeting illusions?

Herb has finished his breakfast, while Dan hasn’t even touched his plate, clearly too tense to eat. We see how reluctant he is to follow Herb.

The backward arrow on the wall is one of the warning signs and significant messages Diane’s subconscious sends her, even in her dream/fantasy, to save herself. Had she turned back and followed the arrow, Diane’s death might have been avoided. But Dan stubbornly continues in the opposite direction. As he sweats approaching his target, he inches towards the corner.

What is it that unsettles us here as viewers? Lynch openly hints that we are about to descend those stairs and confront the monster. Yet, the suspense we feel as we walk down that corridor is palpable. The power of the scene lies not only in the way it builds fear, but in how it teeters us right at the edge before the plunge, making us feel like we’re dancing on the cliff’s edge. We are dragged, irresistibly, toward the inevitable.

And the monster represents the dark truth Betty wishes to avoid – her regret for ordering the hit on Rita, later realizing her remorse. The monster also symbolizes Betty’s failure; in Hollywood, failure inevitably leads here. Notice, too, the monster’s similarity to the Wicked Witch of the East (Oz). Like a mischievous child digging into Hollywood’s darkest corners, Lynch takes no shame in presenting the filth unearthed from this monster’s lair, for he believes in Hollywood’s decay.

We see the monster burning in its own hell. Betty’s two personas merge – the one sitting on the couch and the one exhausted behind Winkie’s. Hollywood’s dream has turned into a nightmare, transforming Betty into a homeless figure in a back alley. As Betty dies, we see the monster’s face again, a reminder that it was part of her all along, representing a twisted personality that drove her to something unforgivable.

The waitress is named Diane:

Diane is Betty’s real name. Why would she assign her own name to a waitress in her dream? (We know that Rita also recalled something upon seeing the name.) Despite breaking a coffee cup and fumbling, Diane shows her kind, nonjudgmental side in the dream. Deep down, Diane longs to reclaim this innocence she once had before coming to Hollywood. Such purity and forgiveness could pull her from her suicidal tendencies.

The Phone

At the beginning of the film, the phone sits beside a lamp with a red shade and an ashtray filled with cigarette butts (a memorable image). The phone rings three times before the scene ends. This call is made to Betty Elms, the idealized version of herself in her fantasy/dream world, highly desired by Hollywood elites represented by Mr. Roque.

In Scene 32, Betty’s phone rings again, although we don’t know who’s calling, as there’s a time skip in the scene. The same phone rings earlier in the film, with the same ashtray and cigarette butts, during the scene when a man says, “The girl is missing.” An alternate reading might suggest Diane is a call girl, and this call in the dream beckons her to Hollywood (after winning the dance contest). Now the caller is Camilla, inviting her to dinner, a symbolic return to Hollywood. The message echoes the one heard at Aunt Ruth’s house when Betty and Rita made the call. Tragedy unfolds as Diane, upon hearing the sweet voice of Rita on the answering machine, reveals her pain. Still, Diane takes the call and, with hesitation, accepts Camilla’s invitation once again, trying to believe in the love she’s searching for.

The Elderly Couple and the Blue Box

Betty’s glamorous arrival in Hollywood contrasts with the actual dance contest she participated in (with the elderly couple beside her when they received the award). In the dream, however, two benevolent figures accompany her (or are they really so kind?).

We sensed something was amiss from the beginning when we saw the eerie smiles of the elderly couple in the taxi. Who are they, exactly? Initially, we see them at the dance contest next to Betty, and then hear that they accompanied her on the plane, only to see them again later when their true role becomes clear.

Dan is somewhat naive, and in reality, he is the only potential witness to a possible murder. He may have grasped the situation, and this understanding might have seeped into his dream. Since Adam is rather innocent, this revelation may have come to him. Notice also the similarity in names: Dan/Diane, suggesting Dan might be one of Diane’s personas. (He’s the one who’s doing it) – Diane’s personality would, of course, protect her by casting the blame on the “monster.” When Dan looks at Herb, he experiences a kind of déjà vu, as Herb is standing exactly as he does in Dan’s dream. Realizing that his nightmare is turning into reality terrifies Dan. Could Herb’s presence be the result of Dan’s narrated story? Do our dreams create and shape reality, or is reality shaping dreams? As Freud suggested, are dreams merely fleeting illusions?

Herb has finished his breakfast, while Dan hasn’t even touched his plate, clearly too tense to eat. We see how reluctant he is to follow Herb.

The backward arrow on the wall is one of the warning signs and significant messages Diane’s subconscious sends her, even in her dream/fantasy, to save herself. Had she turned back and followed the arrow, Diane’s death might have been avoided. But Dan stubbornly continues in the opposite direction. As he sweats approaching his target, he inches towards the corner.

What is it that unsettles us here as viewers? Lynch openly hints that we are about to descend those stairs and confront the monster. Yet, the suspense we feel as we walk down that corridor is palpable. The power of the scene lies not only in the way it builds fear, but in how it teeters us right at the edge before the plunge, making us feel like we’re dancing on the cliff’s edge. We are dragged, irresistibly, toward the inevitable.

And the monster represents the dark truth Betty wishes to avoid – her regret for ordering the hit on Rita, later realizing her remorse. The monster also symbolizes Betty’s failure; in Hollywood, failure inevitably leads here. Notice, too, the monster’s similarity to the Wicked Witch of the East (Oz). Like a mischievous child digging into Hollywood’s darkest corners, Lynch takes no shame in presenting the filth unearthed from this monster’s lair, for he believes in Hollywood’s decay.

We see the monster burning in its own hell. Betty’s two personas merge – the one sitting on the couch and the one exhausted behind Winkie’s. Hollywood’s dream has turned into a nightmare, transforming Betty into a homeless figure in a back alley. As Betty dies, we see the monster’s face again, a reminder that it was part of her all along, representing a twisted personality that drove her to something unforgivable.

The waitress is named Diane:

Diane is Betty’s real name. Why would she assign her own name to a waitress in her dream? (We know that Rita also recalled something upon seeing the name.) Despite breaking a coffee cup and fumbling, Diane shows her kind, nonjudgmental side in the dream. Deep down, Diane longs to reclaim this innocence she once had before coming to Hollywood. Such purity and forgiveness could pull her from her suicidal tendencies.

The Phone

At the beginning of the film, the phone sits beside a lamp with a red shade and an ashtray filled with cigarette butts (a memorable image). The phone rings three times before the scene ends. This call is made to Betty Elms, the idealized version of herself in her fantasy/dream world, highly desired by Hollywood elites represented by Mr. Roque.

In Scene 32, Betty’s phone rings again, although we don’t know who’s calling, as there’s a time skip in the scene. The same phone rings earlier in the film, with the same ashtray and cigarette butts, during the scene when a man says, “The girl is missing.” An alternate reading might suggest Diane is a call girl, and this call in the dream beckons her to Hollywood (after winning the dance contest). Now the caller is Camilla, inviting her to dinner, a symbolic return to Hollywood. The message echoes the one heard at Aunt Ruth’s house when Betty and Rita made the call. Tragedy unfolds as Diane, upon hearing the sweet voice of Rita on the answering machine, reveals her pain. Still, Diane takes the call and, with hesitation, accepts Camilla’s invitation once again, trying to believe in the love she’s searching for.

The Elderly Couple and the Blue Box

Betty’s glamorous arrival in Hollywood contrasts with the actual dance contest she participated in (with the elderly couple beside her when they received the award). In the dream, however, two benevolent figures accompany her (or are they really so kind?).

We sensed something was amiss from the beginning when we saw the eerie smiles of the elderly couple in the taxi. Who are they, exactly? Initially, we see them at the dance contest next to Betty, and then hear that they accompanied her on the plane, only to see them again later when their true role becomes clear.

In Scene 36, Betty’s refusal to confront her own actions and darker side releases the elderly couple, her superego, from the blue box. If Betty doesn’t face her failures and dark side and instead creates an alternate reality, her demons come to confront her. The elderly couple enters this world through an object (the blue box). Who are they, as part of the secret seeping out from the dream? On the surface, they seem like fragments of Diane’s past in Deep River, Ontario, and they also appeared as the grinning couple at the Jitterbug contest, even accompanying her on the plane to Hollywood. In fact, they represent parts of Diane’s superego or conscience. Perhaps they are Diane’s grandparents – the figures who, from childhood, instill morals in us, ingraining themselves in our sense of self and becoming part of our conscience. Diane’s guilt and fear of being caught grow so unbearable that, as she hears the knock on the door, she loses touch with reality, thinking it’s the detective, but it’s actually the elders, symbols of her conscience.

These elderly figures have a counterpart in mythology. Betty emphasizes the woman’s name as Irene, a nod to “Erinyes” (Furies) in Greek mythology – goddesses of vengeance and retribution. They represent terrifying spirits of punishment, dwelling in the depths of hell, relentlessly pursuing wrongdoers. With fierce talons, they create merciless and horrifying torture. Their brass wings make escape impossible, driving the guilty to madness and, often, to death, though they never kill them.

With two demons at her heels, she shoots herself in the head in the bedroom. Then, we see her body lying alone on the bed, and everything goes silent. Blue smoke begins to fill the room.

The blue box symbolizes a memory filled with painful recollections, Betty’s dark memory—a Pandora’s box. The monster had it too. In reality, it’s an insignificant box in the drawer where Diane keeps the gun.

The dream ends when Betty grasps the truth at Silencio. Camilla is no longer in her life, so when she sees the black void inside the blue box, Rita’s presence vanishes. With both Betty and Rita’s personas returning to Diane, everything she once loved has disappeared. When hope fades, the dream ends. Lynch shows us Aunt Ruth’s house through her eyes once more; it’s a dream, and Betty and Camilla never truly entered that house—there’s no trace of their presence, not even the blue box on the carpet.

Let’s leave the final word to Lynch himself. In his book Big Fish, he says, “The box and key—I have no idea what they are.” The blue box and key are, in essence, nothing more than a perverse curiosity of ours as the audience, which is why the hitman dodges the question with a laugh.

Ed & the Hitman

We see two men: our hitman Joe and the pimp Ed. They talk about the accident at the beginning of the film. (Joe, with his unique eye color and appearance, is a nod to Lynch’s admiration for Bowie). Joe is trying to track down Rita, going to a pimp to see if she could be one of his girls. Ed confirms this by telling Joe the story of the accident, which leads Joe to realize Rita might be injured and hiding on the streets, as he later mentions in a subsequent scene. It’s also implied that Ed could be one of the survivors from the car in the initial accident.

The black book—the call book—a world history of phone numbers. Joe needs Ed’s phone book to find Rita, so he focuses on obtaining it. Joe needs the book because his goal is to kill Rita without anyone knowing who he is, which means Ed also has to die. Oops. It turns out our hitman is quite clumsy in the dream, and as we’ll elaborate, Betty doesn’t actually want Rita dead; deep down, she hopes the hitman will fail, sparing Rita’s life.

Anyone else witnessing this in the building, like Ed, also has to go. Yet our hitman is comically inept, making one blunder after another.

Mulholland Drive, crafted by Lynch, is not merely a film; it’s a journey into the depths of the human psyche through cinema. Each scene, every character, every symbol pulls viewers into the shadowy corners of the subconscious. The corruption and pain behind Hollywood’s glamor are not just a backdrop but expressions of the characters’ inner conflicts, identity struggles, and betrayals. By blurring the lines between dream and reality, Lynch ensnares us in a mental trap. Every turn, every vanishing character, every strange symbol creates a reflection; a moment when the dream meets the nightmare, merging reality and imagination into a frenzy. This dark journey guides us to one of the deepest and most harrowing places we can see and feel.

Nil Birinci, April 2022