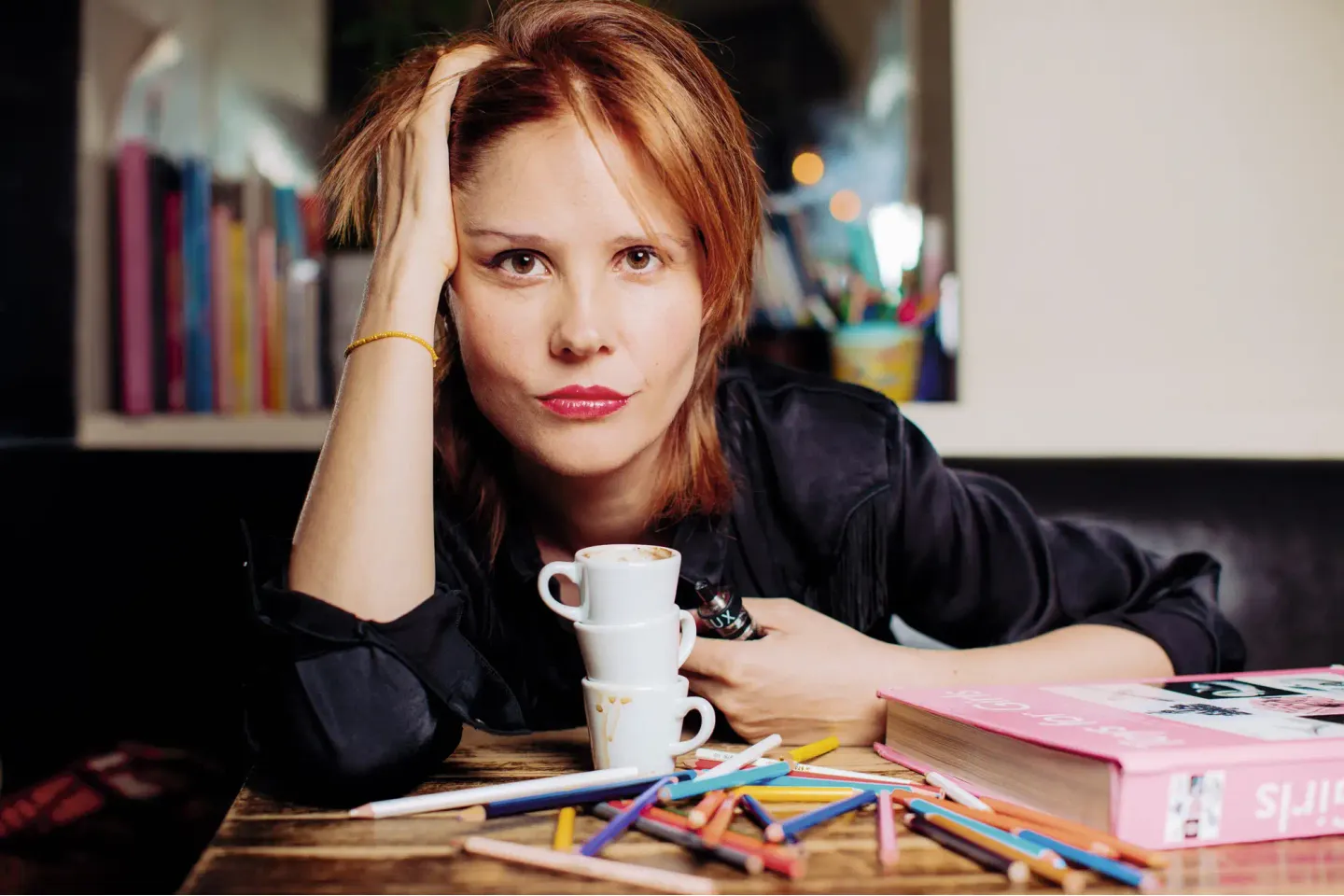

Justine Triet : Female (?) Director

Why do we feel the need to add the label female when discussing artists? Will we ever reach a time when we find this habit as strange as saying male director? While there is hope for near future, today we can still explore the concept of a female director through the work of Justine Triet and her films. In this article, I will divide the discussion into two sections: “Justine” and “Justine Triet’s Films”. By examining these separately, we may better see the relationship. Separating to connect often works.

First, Justine.

Justine

After graduating from the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Justine began her professional film journey in 2007 with the 30-minute documentary Sur Place. The most frequently mentioned fact about her career, at least as of today, is that she is the third female director to win the Palme d’Or, the highest prize at the Cannes Film Festival. I have my doubts about such rankings. When I first heard about a festival dedicated to female directors in Turkey, I had the same doubts. Are we supporting female directors by organizing separate festivals, or are we categorizing them as a separate group in need of support? Maybe fifty years ago, the answer to this question was very clear. On the other hand, how hopeful it is that this answer is becoming increasingly ambiguous.

Justine is not far from activism. As a member of Collectif 50/50, she actively works for women’s equal rights in the industry. In this context, it was expected from political and activist circles for her to give a speech about the place of women in the French film industry at Cannes. Instead of celebrating her second nomination at Cannes as a hopeful victory for women, she dedicated her speech to all young male and female directors who do not have the opportunity to make films, thus defying expectations. While saying that we should now leave the path once opened for us and the opportunities we have to them, she made some of the leading names in the industry a bit angry, although the young people were in tears. Some even called her a spoiled child. (Source) Instead of praising the French cinema industry, which is in a much better place compared to other countries (liberté, égalité, fraternité!), for her stance on the side of young people going through one of the toughest times in cinema history, I take my hat off to her. It is not difficult to see that the revolutionary and innovative tradition of France -the cradle of cinema- needs young people. On the other hand, I think it deserves appreciation that filmmakers at the peak of their careers do not forget this truth despite their egos being inflated by those around them.

Even though Justine does not prefer to use the label of a female director for her image, she is very successful at reading PR codes. She skillfully uses the intriguing charm of the relationship between fiction and real life, reflecting their private lives as a filmmaker couple in her interviews. At this point, we can highlight that in recent years, filmmaker couples where the woman is in the foreground have become more common. Looking back, we are used to seeing actress-director couples in cinema, such as Godard-Karina, Bergman-Ullmann, Fellini-Masina… and the list goes on. After relationships where the man’s fame usually overshadowed the woman (Bergman undoubtedly thought he was complimenting Ullmann by saying, “You are my Stradivarius”), examples where the fame of female directors overshadowed the man began to increase. Although the most well-known is Greta Gerwig, who could even overshadow Noah Baumbach, there are many examples. Justine, who writes her films’ scripts together with her husband Arthur Harari, and gives him small roles in her films, is one of these couples. Together with her two children and her husband, with whom she works in the same industry, she is now in a period where the young and promising female director phase is far behind, experiencing middle age while swimming in international waters with major productions. As a mother of two, she openly talks about the difficulties of having to work long hours in a competitive industry, despite being known as a hyperactive director. She does not hide her amazement at the stories of women around her who have decided not to become mothers due to the difficulties they experience in their careers and lives, and the fact that these topics are rarely discussed and find little place in cinema. (Source) I will relate the reflection of her life with her husband and children in her films to the heading of her films and leave this topic on standby here for now.

There is not much information about Justine’s professional career and life with her husband before her career. Her father, Raphael Doko Triet, has been a member of the Buddhist (Zen) community in Paris since a very young age. After the leader of the Paris Dojo passed away, he succeeded him, and in 1995 he became the founder of the Lisbon Dojo. (Source) As a result of Zen teaching and the roles he undertook, we can conclude that he was not a classic father figure and Justine Triet did not grow up in a conventional family environment. In her interviews, she talks about her mother’s difficult life with three children, two of whom were not her own, and the void her father created in the family and, consequently, in her life.

In her early youth, Justine was interested in painting. She describes her paintings from that period as descriptive, a bit strange, and expressionistic. After meeting Virgil Vernier at art school, she entered the film industry through him, and things developed from there. (Source) Virgil Vernier also appears in her first feature film cast, just like her current husband, Arthur Harari. Throughout her film career, Justine builds long-term relationships with the people she works with, including child actors. Her long-term producer Marie-Ange Luciani describes her working style as follows: “Justine does not work like others. She turns filmmaking into a collective art form.” (Source)

To conclude the Justine section, while connecting her personality and private life with her films, we can briefly list the key relationships we will use as follows :

(1) Raised in a fatherless family, her mother is a woman who raised three children alone

(2) Her comment on the paintings that marked her entry into art: descriptive, bizarre, and expressionistic

(3) She establishes long-term relationships with the people she works with in her films

(4) A hyperactive director and mother of two. She has a special interest in topics like working mothers, midlife crises, and marriage

(5) An activist. Initially advocating for women’s rights, she now prioritizes young filmmakers

Justine Triet Films

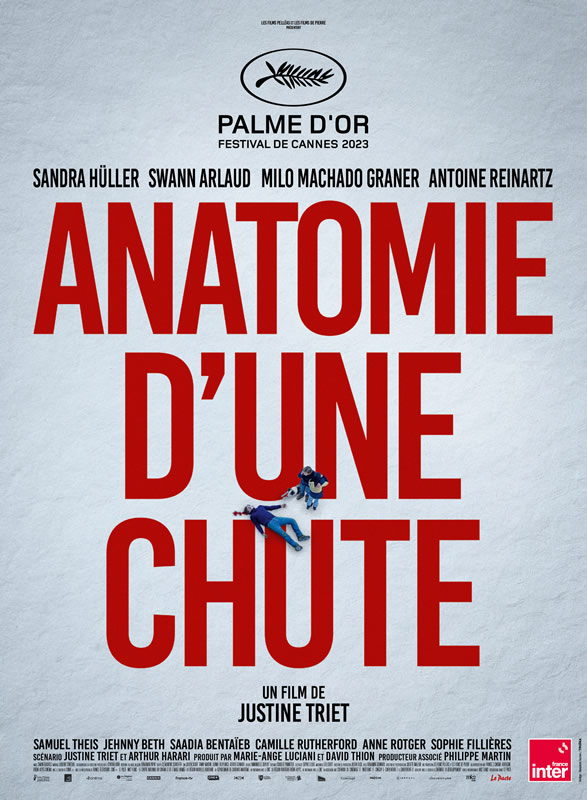

At the beginning of this article, I mentioned that we could examine Triet as a female director. If we start listing the reasons under this section, the choice of main characters would undoubtedly take the first place. Is it a coincidence that all her films’ protagonists are women and the entire plot revolves around them? Or does Triet’s focus always on women because she draws stories parallel to her own life in her films? I will be a bit more assertive and go so far as to claim that the main characters in her five films are the same woman living in parallel universes. Although not as multi-layered as Sandra in “Anatomie D’une Chute” the shared traits among Laetitia (Vilaine Fille Mauvais Garçon, 2012 & La Bataille de Solferino, 2013), Victoria (Victoria, 2016), and Sibyl (Sibyl, 2019) are so numerous that I think we can assert this. Over the years, we observe that the characters in her films become more mysterious and complex. The positive impact of her characters’ development on her films and their contribution to her success cannot be ignored. Just as a woman transforms her character in her early youth over the years with every relationship, experience, and decision—like building a whole body by adding muscles, flesh, and skin over a skeleton—Triet’s characters in her films, though they share a common skeleton, gradually acquire a body and become more visible over the years. Triet describes her characters in an interview: “I love writing complex female characters. They first represent order, morality, and good little soldiers. Then I break them down and watch them fall. While this is very common with male heroes, we are not so used to seeing a woman in this way” (Source)

After this introduction to Triet’s characters, to better understand her latest character Sandra (Anatomie D’une Chute, 2023) as of today, in other words, to delve into her skeleton, we will meet Laetitia from the film Vilaine Fille Mauvais Garçon.

The short film, which lasts 30 minutes and covers events from one evening to the next morning, begins with the image of a lonely and introverted man living in Paris, a penniless painter, depicted through a glimpse of his buttocks. I don’t know if this shot of the buttocks, which we will see many times in Triet’s subsequent films, has any meaning as Triet’s signature, but I will skip this detail for now since it doesn’t relate to Laetitia. It is evident that the male character in the film, with his pennilessness and social awkwardness, is inspired by Justine’s friends from her early youth when she was painting. In fact, she mentioned in a panel that the person playing the male character was also her friend in real life, if I remember correctly. The male protagonist is a bit odd, just like Justine’s early paintings. While we are included in his evening, we meet Laetitia, a beautiful and lively young woman who recently broke up with her boyfriend and is trying to live life to the fullest. Her fear of missing out on life is apparent in every moment, and living fully requires a genuine effort for her. Laetitia, who cannot leave the house without abandoning her dependent brother, cannot be said to be completely free and reckless. Despite her initial appearance, she differs from the image of the free and lovable young woman often seen in romantic comedies. Personally, I find Triet’s real success in the small details that make Laetitia and her struggle feel authentic. The first example that comes to mind is the elastic band on her arm while dancing. Seeing the essential accessory of a woman going out dancing to tie up her sweaty hair on Laetitia’s wrist or noticing her adjusting her dress’s neckline before taking off her coat, or her almost nonstop talking at the brink of a nervous breakdown without pausing for breath, even though she notices the man getting bored and looking around, or her immediate return to reality when her phone rings while crying—these details we encounter during the short film make the character and story feel more real. Even though it seems like a romantic comedy on paper, in this story where Laetitia tries to balance life and responsibilities, Triet manages to tell as much of a story as in a feature film. Undoubtedly, there is also the influence of the gaps we fill with gestalt principles.

A year after her short film, her first feature film La Battaile de Solferino shows Laetitia again, now a woman with two daughters at a turning point in her career, trying to balance childcare and professional success. Again, we see a woman caught between her desires for herself and what is expected of her due to her responsibilities. This film is also the first where Justine worked with her partner, Arthur Harari, who plays the lawyer Arthur and appears in several supporting roles in her subsequent films.

Due to budget constraints, the film could not obtain permits for real rally footage, so many scenes have a documentary feel. The success and impact of these sections make it possible to say that budget constraints were more of a blessing than a curse for Triet. The film, a blend of documentary and fiction, is highly praised for bringing a new breath to cinema with her debut film that showcases her early documentary experience. It always amazes me how things that seem like bad luck in life turn out to be turning points over time. Returning to the film, the documentary feel of the rally also reflects on Laetitia’s personal life. Triet’s dialogues are very natural, and like in her first short film, she does not skip the fine details that enrich her character, successfully turning Laetitia into a nearly flesh-and-blood woman. For instance, in the scene where she meets a friend after a long and exhausting day and takes a night walk, her response fatigue to the friend who says “You lack imagination” was very successful. The look Laetitia gives him as if to say “With your pretentious lifestyle, you’re so far from my life that I won’t even activate a single cell in this tired and worn-out body to explain myself to you” was very well done. In another scene, while struggling to get out of the house among the cries of crying babies, or while pulling her dog for a walk even though she took it out for a pee, Laetitia is no different from any woman torn into ten thousand pieces between her desires and responsibilities. She is like a little soldier fighting in a life without the children’s father, just like Justine’s real-life mother. She has to rely on support from other people around her, like her babysitter or neighbor, to sustain her life, which again reflects the collective lifestyle Justine adopts while making her films.

Triet adds this comment about the realism of her characters in the film: “People who want to make realistic films believe in the ideal of purity. On the contrary, what interests me is the exact opposite of purity in both form and content. My characters are filthy and mismatched people, children who have grown up in panic and lost their ability to live. I prefer what I see in their roughness to ghosts and modern stories. Laetitia and Vincent are going through tough times, monstrous and violent times, but they are alive!”

After praising Triet for the realism of her characters, I will move on to some unpleasant details about real life behind the camera. Seeing children in the film in an environment where people smoke, walking barefoot on carpets where people walk with shoes from outside, and crying continuously and in real-time was very disturbing. After seeing these overly realistic scenes of babies crying, unlike in other films where we hear baby cries in the background, I thought about how the filming must have turned into torture for the babies who had to be made to cry repeatedly in a smoky, dirty environment. Then I imagined Justine and asked her, “Today, how do you view children who have no choice working in an environment like this in your film? As a mother of two now, if you were filming this with your own babies, would you still shoot under these conditions?”

Of course, Justine cannot answer this question, but now I will turn to myself and ask, “If Justine were not a female director and a mother, would you still ask her this question?”

I believe I have clearly demonstrated the reason why we still refer to her as a female director and an effort from both a director Justine and a mother Justine. Sometimes questions reveal reasons more clearly than answers.

After her first feature film was nominated for a Cesar, Triet was listed among the promising directors. The expectations rising from her were met with her second film, Victoria released in 2016. Although the film is classified as a romantic comedy, it is known globally as In Bed with Victoria. The chosen title reflects Victoria spending most of her time at home in bed. If we interpret it more deeply and a bit boldly, it may also reflect her filling the emptiness in her life by having sex. Victoria, like Laetitia, lives alone with her two daughters, trapped between being a lawyer and a mother, and even though it is not very apparent, we can feel the existential angst burning inside her, caused by a sense of dissatisfaction.

While far from being an idealist about her career as a lawyer, which she clung to with extraordinary effort throughout her life, we can clearly feel the suffocating boredom that takes Victoria’s breath away, exacerbated by her alcohol problem and fleeting relationships.

The turning point in her suffocating life occurs at her friend’s wedding dinner. Watching her ex-boyfriend and his new lover engage in romantic and exaggerated displays of affection, Victoria looks on the scene with jealousy, so to speak. Isn’t it always like that? When we see people we were once involved with, whose paths diverged from ours for some reason, years later in a completely different place, perhaps advanced and happy, we turn to our own lives and ask, “What am I doing?” Although we hear this internal and unspoken question, the breaking point that night is not this question. Upon hearing news from her ex, she learns that he has been accused of injuring the woman he was with in those exaggerated displays of affection that night. Her ex, who needs a lawyer, trusts only her and sees her as the savior who can get him out of this big trouble. Even though she knows it is meaningless professionally, perhaps due to the emptiness inside her, she heeds the call. Throughout the series of events that will develop and temporarily distance her from her profession, there will be two people who stand by her and support her: her friend, who is also a lawyer like herself, and her former client, whom she reencountered at that wedding dinner. Thus, just as luck and misfortune came simultaneously in Triet’s life, with misfortune later turning into a chance of a lifetime, Victoria will encounter both the trouble of her life and the peace she seeks on the same night. Like the good and bad messengers in mythology, two messengers from the past will drag Victoria into a plot that first gets entangled and then resolves, as in classic romantic comedies.

Despite not using classic codes, the film is ultimately a romantic comedy. Even though it proceeds as a parody, we have the opportunity to observe Justine Triet’s perspective on a criminal case. While the legal process progresses with the public reactions due to its media coverage, different perspectives on crime, criminals, relationships, and women are reflected, and the first signals of her latest film, Anatomie D’une Chute can also be seen. On the other hand, since the themes of the main character Victoria’s romantic relationship and the mystery of the criminal case do not fully mix like water and oil, and perhaps due to the barrenness of the script, Triet is still quite far from reaching her potential.

In the film Victoria as in her next film Sibyl while children are not the main characters but more of a backdrop supporting the story, it must be noted that the relationship between the character and the children deepens with each film. The children go beyond being distracting figures representing the woman’s responsibility of motherhood, becoming individuals who shape the character’s life and engage in dialogue. Particularly in Sibyl wanting to be a mother despite her then-partner’s reluctance to be a father will be a significant turning point in the main character’s life. When Sibyl, who has to raise her child alone, sees her ex-lover as a father years later, it almost depicts the resolution of her past traumas. Sibyl, who was not chosen as a mother by the man she loved and was passionately attached to, revisits her past repeatedly while helping a young actress who seeks her assistance, oscillating between being a mature and healthy individual and a psychologically wounded woman living in the past.

At this point, we can note that the name Sibyl, the titular character of the film, is known in mythology as a wise woman. The story goes that Sibyl appears before the ruler of the time with her nine books containing the secrets of the universe and offers to give them to him for a price that she finds reasonable but the ruler finds absurd. When the ruler deems the price too high and refuses, Sibyl burns three of the books and offers the remaining six for the same price. Angered by her audacity but increasingly curious about the mysterious information in the books, the ruler refuses again. This time, Sibyl burns three more of the remaining six books and again offers the remaining three for the same price. Realizing that all the books will be lost, the ruler, driven by his growing curiosity, agrees to pay the price he initially refused for the nine books. If we look at the connection between the wise woman Sibyl in this story and the main character in Triet’s film, we can see that Sibyl is the person to whom the questions of many women today, faced with the choice of being or not being a mother, are directed. Like her mythological namesake, the Sibyl in the film does not easily give the knowledge she possesses to those who seek it. Her attitude toward this knowledge is particularly noteworthy. Sibyl is more concerned with winning her claim than with the knowledge reaching the seeker. I find the process between Sibyl and the young actress particularly interesting from another angle. The unchanging rule of life is that wisdom demands an invaluable price, namely one’s youth. A mature person has paid the price of knowledge with the bitter experiences of their youth. From the perspective of the young and inexperienced, there is no guarantee of the truth of any knowledge not gained through experience. Although the young actress in the film follows Sibyl’s words unconditionally, Sibyl is utterly lost in her own life. As viewers of the film, we are left unsure whether to laugh or be sad at this absurd irony.

When Justine made this film, she had crossed the 40-year mark in her life and entered a period where we can no longer call her a young woman, though she is not old. The mature-young person relationship, which had become more prominent with younger side characters than the main character since her first films, becomes even more pronounced in this film. We can now stop and ask, “What is Justine, known as a brilliant director whose every film is eagerly awaited, offering to the young filmmakers around her?” On one side, young filmmakers have their inexperience, unpaid dues, and yet-to-be-made mistakes, but on the other side, they have a promising future, countless mistakes they can make, and most importantly, their priceless youth. Youth is the highest price to be paid for knowledge. Does Justine long for the youth left behind after paying this price? We can recall from her speech at Cannes that she uses this longing, not with jealousy but with strength, to pave the way for them.

Returning to Triet’s film Sibyl it becomes increasingly difficult to distinguish how much of the real-fiction confusion in the film is a deliberate mystery created by Triet and how much is a product of the main character’s disturbances. This difficulty shifts even more when a second character, who reflects the main character’s desires and disappointments, is both her patient and the main character of her book, the young actress. Additionally, it must be noted that while Triet is inspired by real stories when writing her scripts, she prefers to transform reality. While we can’t confirm if Triet, dealing with the actors’ whims that make completing a film nearly impossible, has ever expressed her own passive-aggressive feelings by saying “I hate you” to them, it is certainly possible. Nevertheless, adhering to Triet’s interviews, we can say that while the roots of the characters and stories in her scripts are nourished by her life and experiences, what gives them their true power is her ability to transform this reality. Sibyl’s work of transforming reality while writing her book in the film is somewhat akin to this.

With the film “Sibyl” Triet’s development in cinematography and acting direction cannot be overlooked. She succeeds in capturing frames that will effectively bring the most striking scenes of the script to the screen in both outdoor and close-up shots. While I find the film technically strong, I believe the complexity of the script turns into an element that undermines the main emotion and story. On the other hand, we cannot deny that the film marks a turning point in her encounter with Sandra Hüller. Ultimately, in our journey from the past to the present, we started with the character Sandra.

When we come to her latest and most successful film across all award arenas, Anatomie D’une Chute and return to the character Sandra, whom we began analyzing in Triet’s films, we encounter numerous interviews given by Justine on various platforms. It is no secret that she wrote the key character in the film with Sandra Hüller in mind, designed a plot suitable for her bilingual character, and that Sandra Hüller took French lessons for this film. Another often-discussed detail is that Triet and her husband Arthur Harari wrote the film’s script during the pandemic, in a period when they were closed off from the outside world in their small universe. The atmosphere of the writing period also shapes the film’s main atmosphere. We can feel the sense of confinement during the pandemic in Sandra’s life, spent in a French countryside far from her home country. The carefree and fun days spent with the husband she married with great passion are in the past, replaced by repetitive days within the written and unwritten rules of their marriage. When their child’s special needs are added to this change in their relationship’s nature, the marriage becomes a prison for both of them. The remote and dull environment in the countryside does not help this situation. As a result, while writing an anatomy of a fall in her latest film, it can be said that Triet also reflects the metaphorical fall of a marriage.

When we take a moment to step outside the film, it’s possible to say that the anatomy of the marriage depicted in the film resembles Noah Baumbach’s “Marriage Story” (2019). Especially when we listen to the audio recording of the argument between Sandra and her passive-aggressive husband, who blames her for the failures and entrapment in his life, we can feel the separation experienced under the unifying roof of marriage to our core. The transformation of two people, who joined their lives with love and passion, into each other’s greatest destroyers, and the bottomless chasm that comes between them, is a very familiar and much-discussed topic. Despite its familiarity, it has never lost its popularity due to the evolving nature of these discussions today. It can be said that one of the most successful examples regarding the nature of marriage came from the legendary director Ingmar Bergman. We remember making a substantial entry into this topic with Bergman’s “Scenes from a Marriage” (1974) almost fifty years ago. Before moving on to the film he transformed from the TV series in 1974, it is appropriate to pay tribute to Bergman’s female character in cinema. Until Bergman, women were depicted in such a one-dimensional manner for years that, apart from a few sparks, women were constantly repeating themselves as a uniform character, like a two-dimensional cardboard cutout. Women, usually told by men, existed only to fall in love, to be loved, or for motherhood. Bergman, however, gave his female characters flesh and bone, breathing soul or whatever you call it into them, making him a revolutionary not only in cinema but also for female characters in cinema.

In “Scenes from a Marriage” although the marriage scenes crafted by his skillful hands are essentially an analysis of a marriage, it can also be viewed as the story of a woman who, having been unable to assert herself and never fully knowing who she truly was throughout her life, discovers herself after her marriage ends. When Baumbach continued this legacy with “Marriage Story” in 2019, he modernized the story, creating a more talkative and contemporary female character. Although not as profound as Bergman’s, Baumbach’s contemporary perspective on the existence of women within and outside marriage is commendable. The film can also be seen as the spark that ignited a series of productions in subsequent years. This topic was rewritten with the cultural codes of African Americans in Sam Levinson‘s “Malcolm & Marie” in 2021, and in the same year, Hagai Levi‘s mini-series “Scenes from a Marriage” premiered on HBO. In Levi’s series, he directly adapted Bergman’s script but had the characters switch places as a bright idea, giving the experiences of the man in the seventies to the woman and vice versa. The transformation the female character underwent over fifty years, progressing as a homage to Bergman, from the character’s names to their positions on the couch, is very striking. From this perspective, the marital conflict transformed into a script by Arthur Harari and Justine Triet from their lives, confined during the pandemic, can be seen as a link in the chain mentioned above. However, the most significant new addition to the chain brought by the film is the child who becomes a character in his own right. This new and powerful element was a crucial dimension missing in Bergman’s film, which we consider the first link in the chain (perhaps reflecting Bergman’s choice to especially avoid his children in his films, as he particularly overlooked them in his personal life). We noted that children, initially just a backdrop in Triet’s early films, have gradually increased in impact over time. This growing impact adds depth and strength to the film with the highly complex and mysterious character of Daniel, the child protagonist in “Anatomie D’une Chute”. If we liken the turbulent relationship between Sandra and her husband to a stormy ocean, Daniel is like a powerful whirlpool beneath the surface, not immediately visible but with a potentially stronger effect than the storm on the surface.

Additionally, we can feel the crime-criminal perspective that Triet hinted at in “Victoria” down to our bones in this film. Triet, who did not share with the lead actress Sandra Hüller whether she was guilty or not, keeps the script equidistant from all possibilities, maintaining the audience’s interest at its peak with her maneuvers. While everyone who watches the film has an opinion about Sandra and the fall incident, no one can say for certain what the truth is. Just as we can never know the truths behind the stories we hear in daily life, apart from the primary witnesses of the incident, concepts of truth, crime, and criminal vary surprisingly according to the perspective we stand from. When personal experiences, character, and other factors are added to the perspective, the possibilities become endless. After her unsuccessful attempt filled with limited possibilities and knots that left the audience lost in the mystery in “Sibyl” Triet seems to have finally found the right formula with “Anatomie D’une Chute”.

The young-adult relationship that Triet began to touch upon in her recent films takes form in the young journalist who conducts the interview on the day of the main event in this film. Although this duality is not heavily emphasized in the flirtatious conversation between her and the young journalist, I have a strong intuition that Triet will deepen this relationship in one of her upcoming films.

To summarize quickly, it is not surprising that Triet, who has taken a step further in technical and actor management improvements, added an extremely successful script with strong characters, dialogues, maneuvers, and elements of mystery, along with a powerful cast led by Sandra Hüller, to create one of the most successful films of 2023.

Conclusion

In examining Justine Triet’s cinema journey with female protagonists and her as a female director, I tried to establish the relationship between art and the artist. Although the appeal created by the reality in her scripts played a role in my choice of this path, my belief in the strength of the bond between life and art was also influential. Oscar Wilde’s aphorism “Life imitates art far more than art imitates life” describes, in my opinion, the seduction between life and art. To me, it does not matter much who seduces whom.

It is delightful to follow Triet, who continuously develops her characters from Laetitia to Sandra, adds strong elements to her stories, increases her mastery of using mystery, and broadens her perspective. However, I must admit that I do not like her predictability. Instead of imagining her in a bicycle race as last year’s champion, I envision her with her eyes closed, feeling the wind on her face while riding. This would be unexpected and memorable. It is usually such things that add the real excitement to cinema.