Art References in Mulholland Dr.

David Lynch, as one of the key figures in surrealist cinema, has constructed his artistic background by drawing from both classical and contemporary movements. While studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Lynch was heavily engaged in visual arts, such as painting and sculpture. During this early period, expressionist and abstract art approaches became crucial influences that shaped Lynch’s cinematic language. Dark, dreamlike images and the exploration of the subconscious are present in both his visual arts and films.

“Mulholland Dr.” (2001) stands out as one of Lynch’s most iconic works, reflecting the dream-like reality in cinema. The film is marked by the strong influences of surrealist art and abstract narrative forms. Illogical and layered imagery, reminiscent of the works of Salvador Dalí and René Magritte, permeates Lynch’s storytelling. The film immerses the audience in a continuous process of interpretation and questioning as it deals with themes of the subconscious, identity loss, and the conflict between dream and reality. Lynch’s set designs and character portrayals are inspired by Edward Hopper’s paintings, which convey themes of isolation and ambiguity; the allure and danger of Hollywood echo the somber images of American reality depicted by Hopper.

In this context, it is clear that the artistic references in Lynch’s masterpiece “Mulholland Dr.” deserve a detailed analysis.

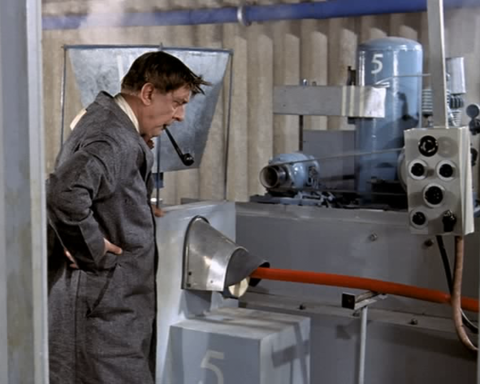

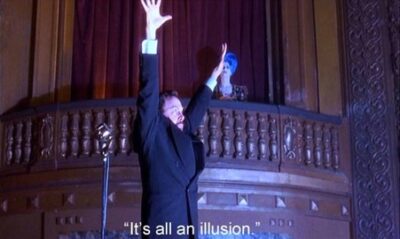

The Club Silencio scene. According to Lynch, we, the people of the 21st century, live in a postmodern world of representations. Life itself has become intertwined with cinema, music, and visual art, transforming into our reality. Our lifelong struggle is to control those representations, that false reality. Simultaneously, we stand against the world and our own lives, our own truth, as if we were a successful actor or director controlling the narrative. The self is split, just like Rita and Betty, as both a representation and the controller of representation.

The design of Silencio also references Edward Hopper’s “Two on the Aisle” (1927). We see the extent of Hopper’s influence on Lynch in subsequent scenes, but first, let’s examine what elements have carried over from Hopper’s paintings into Lynch’s films:

- Dimly lit images and muted colors

- Somber American realism

- Stylization of refined images

- Moving beyond realistic presentation to heightened expressions of mental states

- Focus on the fundamentals of landscape narrative

- Mise-en-scène stripped of unnecessary details with minimalist decor

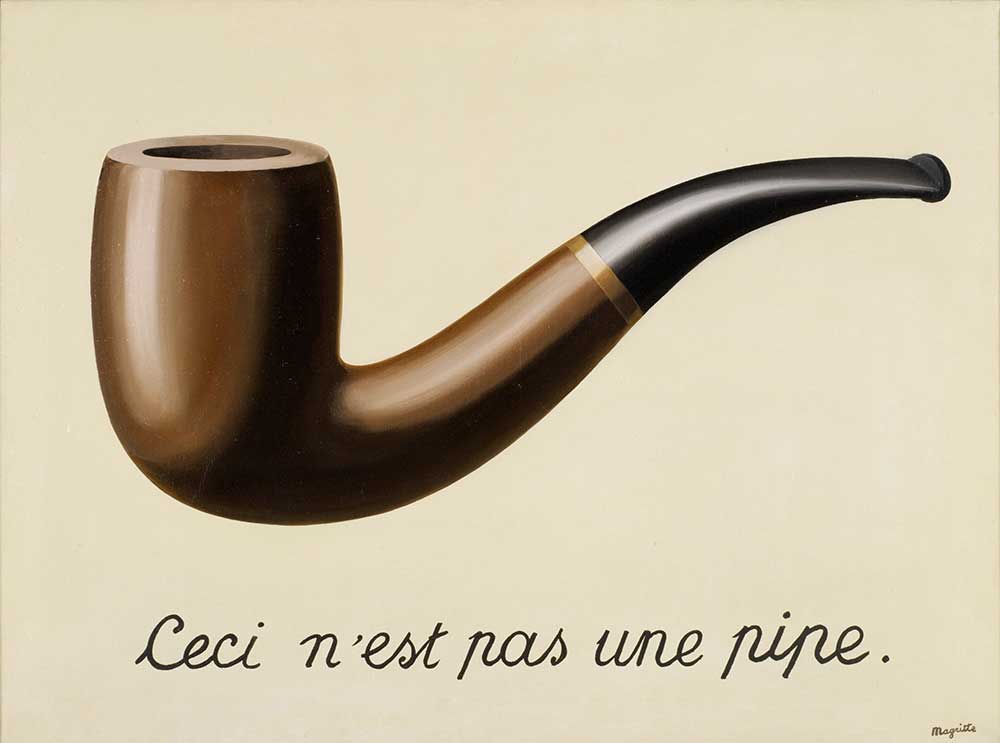

“No hay banda”—there is no band; this is not a concert = “This is not a pipe” (René Magritte). Silencio heightens the audience’s awareness, showcasing the qualities of postmodern cinema: everything we shouldn’t see or hear in a performance is laid bare on this stage. Everything is fake, announced by a presenter who is supposed to cover it all—no band, all playback, spotlights, the relativity of truth, the singer who faints and is dragged offstage. The off-stage world intrudes onto the stage.

—

In Diane’s apartment, the surprisingly sparse personal belongings give it the character of a hotel room or rented house. Here, two references to Edward Hopper’s paintings are evident. One is “Morning Sun,” and its nightmarish version. It symbolizes the mediation between inner reality and the outside world. It represents the perceptual process after waking up—when we open our eyes to reality after a dream. Diane’s awakening from her dream. This image also appears as a poster in the film’s restored Criterion version.

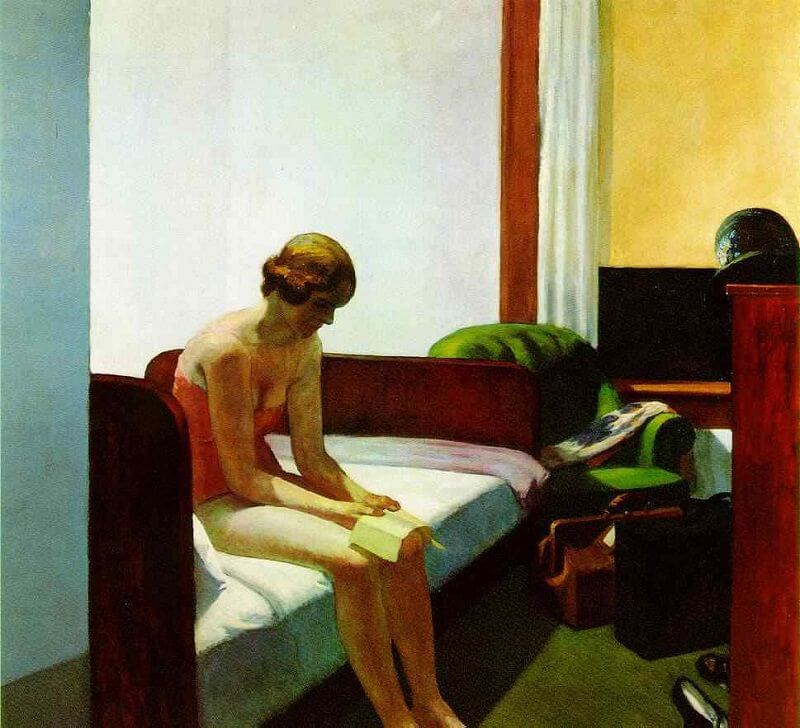

The other is Hopper’s 1931 “Hotel Room,” which strongly conveys his preoccupation with loneliness, much like Diane.

—

The painting on the wall is the famous 16th-century work “Beatrice Cenci” by Guido Reni. Beatrice, a Roman noblewoman, was a victim of her father’s incestuous advances (some readings suggest Betty may have experienced something similar, given we never hear about her parents). Beatrice subsequently hired two hitmen to murder her father and made it look like an accident, becoming a symbol of lost innocence and inspiring numerous artworks, books, plays, and even films that capture her story. This symbol merges with Betty for a third time.

—

Now, let’s examine the unsettling nature of both “Mulholland Dr.” and “Twin Peaks.” The inspiration comes from Francis Bacon’s “Seated Figure.” The work captures the artist’s striking and distorted depictions of the human form, expressing inner turmoil and emotional tension. Typically using red, brown, and dark tones, the painting gives viewers a sense of the figure’s disturbing and uneasy nature. Bacon highlights deformation and motion, emphasizing the fragility of human existence, reflecting the artist’s interest in existential anxiety and decay—a sentiment that needs no further explanation in Lynch’s case.

—

The house design draws inspiration from Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi’s works, particularly the Strandgade series like “Moonlight” or “Interior.” However, in terms of colors and content, it also evokes Hopper-like scenes.

—

The house’s interior is mesmerizing, embodying the Golden Age of Hollywood. The paintings catch the eye, featuring both classics from the 15th-17th centuries and modern artworks side by side. Curtains, wall patterns—everything seems like a work of art, suggesting that the aunt might be an art enthusiast or collector, much like many Hollywood stars.

A painting in Adam’s house appears abstract, contrasting with Aunt Ruth’s classical and modern artworks, representing contemporary art. Comparing the two houses reflects two eras of Hollywood: Aunt Ruth’s home symbolizes Classic Hollywood’s Golden Age, while Adam’s represents today’s postmodern Hollywood.

—

The painting, given to Aunt Ruth as a gift from a couple, has both their signatures in the lower-left corner, indicating a celebration. The message reads: “Huang Kaiqiang and Liu Zhu respectfully congratulate you!” This painting underscores Aunt Ruth’s success.

—

A cabinet design references Vanessa Bell’s “Bathers in a Landscape.” The painting, which evokes a sense of abstract and distant loneliness, features figures with indistinct facial details, offering an anonymous human condition that prompts contemplation on identity, privacy, and inner peace. Sound familiar? Yes, it mirrors Rita.

—

Betty watches over Rita as she sleeps, highlighting Betty’s protective nature toward Rita. The painting by the bed, depicting a white feather or wing, underscores her sensitivity.

–

Winkie’s Restaurant is another nod to Hopper.

—

The painting behind Adam refers to Our Lady of Guadalupe (16th century), symbolizing divine salvation, potentially ironic given Adam’s situation and his lack of faith.

—

A painting in the background likely depicts a female figure from the early days of film, resembling Muybridge’s “Motion Study” images, evoking the isolation and namelessness of women in Hollywood’s history. This woman is not just Betty; she represents the female film star persona in Lynch’s films, like Laura Dern in “Inland Empire.”

—

Through its striking transition from images to moving visuals, “Mulholland Dr.” masterfully connects visual arts with cinema, echoing the surrealist tradition by exploring dream sequences and the subconscious. Lynch expands cinematic aesthetics, drawing inspiration from classical paintings; the sense of isolation and vivid lighting in Edward Hopper’s works shapes the film’s Los Angeles backdrop. The Magritte-like illogical scenes guide viewers through layers of meaning, turning Lynch’s cinema into a visual experience where still images come to life, taking the audience on a mental journey.

Nil Birinci