The United Kingdom has a climate where social realism thrives. If the Punk movement is one of the most distinctive herbs of the lands with abundant rainfall and a deep-rooted working class, I can call Andrea Arnold the Punk of cinema. This is a very easy definition, but I always say that the first things that come to mind are usually not far from the truth. When I think of the original films she has produced since the early 2000s, I am always excited to see the world from Andrea Arnold’s perspective, what has remained the same and what has changed in Arnold’s films over the years. As I read, I also come across interesting information I have never heard of. What was the project that brought Lars von Trier and Andrea Arnold together? What about the one where she met King Charles? Did Andrea Arnold, the Punk of cinema, share the ironic fate of being honored by the crown, like Vivienne Westwood being given the title of Dame?

I must calm my excitement and start from the beginning.

Places

Born in Kent as the first child of very young parents, the two most important autobiographical elements used by Andrea are places and characters. When I took a quick look at the places where Arnold spent his childhood, these places, where ugliness prevails but also hides beauty, seemed quite familiar. No, I have never been to Kent before. It is obvious that there is an acquaintance that started with the scenes in her films. As she remembers from his childhood, I feel as if I have created my own memories in the outdoor spaces that Arnold frequently includes in her films. I read somewhere that she developed a dual approach through landscapes and the poetry of space. What is meant by the poetry of space must be the feeling that we are witnessing a childhood memory. If childhood memory is like a dream, the closest thing to poetry, then I am trying to say the same thing with different sentences. On the other hand, I wonder; do children establish a different bond with places than we adults? So why does the childhood we remember in adulthood constantly change?

Tim Endensor has provided a more detailed and more insider, that is, British, definition of the places that I define as ‘places where ugliness predominates but also contain beauty’, ‘places that give the feeling of witnessing a childhood memory’:

‘Generic English contemporary landscape replete with a host of mundane settings that diverge from any notion of a romantic urban and rural Englishness. There are elevated sections of motorway that look out onto low-key, semi-industrial town-scapes, with the banal kinds of fencing and roadside fixtures that extent out of many large towns and cities across the UK. There are poorly maintained post war housing estates, with their scruffy communal play areas and run-down stairways and balconies, and the low-key shopping precincts typical of many English urban areas. They certainly convey a sense of grittiness, this is not merely symbolic but it is embedded in the ways in which such environments are felt and sensed and chimes with prior experiences of actual space. ’

Physical locations and their memory-like nature become the most important strength of Arnold’s realism. When we combine other important and common elements in her films, we will be able to reach a more comprehensive definition of Andrea Arnold’s cinema, but not yet.

Guiding Image

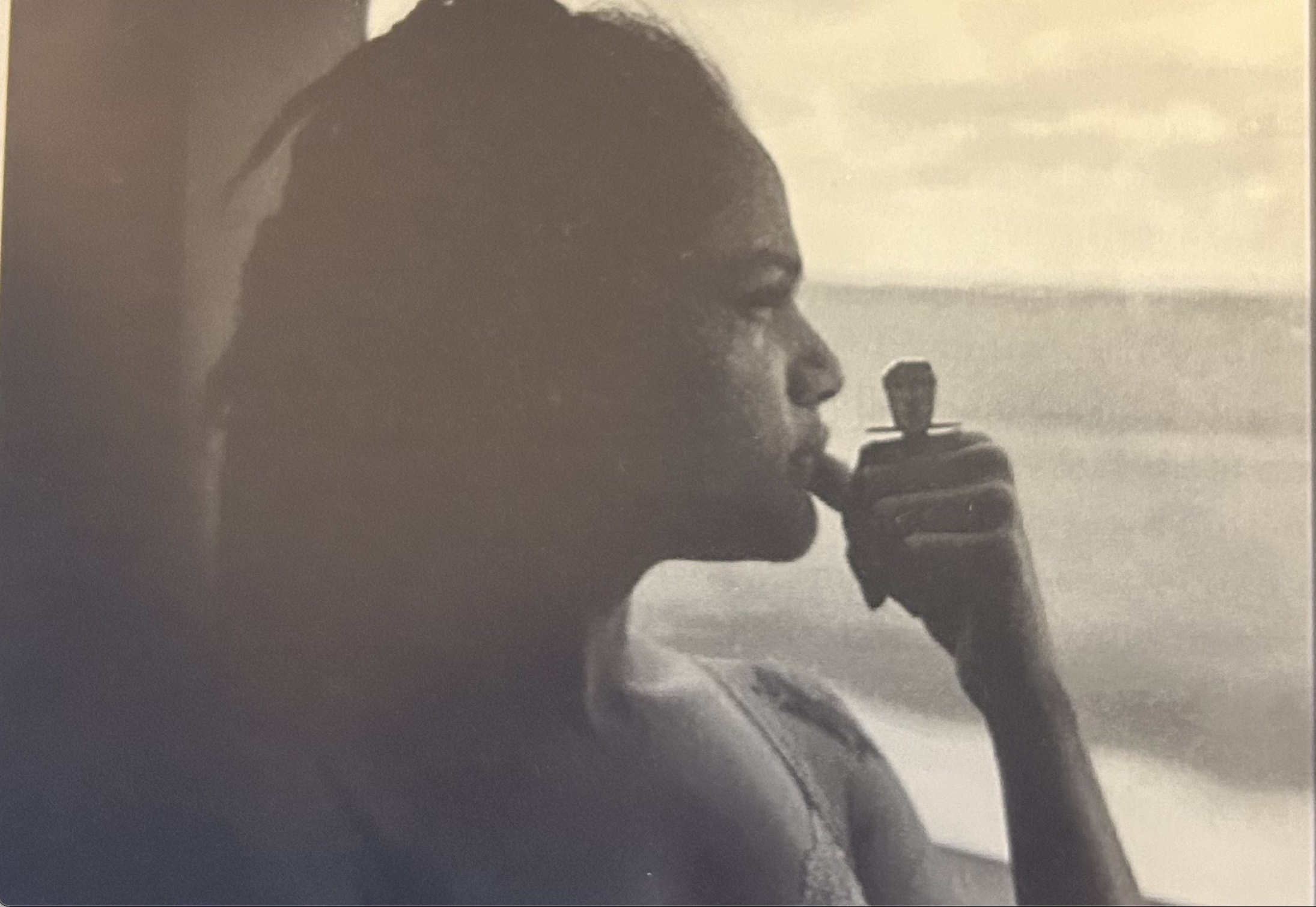

Does the narrative come first or the image? For Arnold, the answer to the question is the latter. Arnold says that she always starts writing with an image. “Normally, I start writing with an image that bothers me, and this image that I feel compelled to go there and explore, is a great way for me to start writing and has become something that haunts me now.” From these words, we can conclude that Arnold’s films are more of a visual starting point than a structural, ideological or emotional trigger. The guiding image for her film Wuthering Heights (2011) was an image of a giant animal climbing a swampy slope. When he looked carefully, he realized that it was a man carrying a dead rabbit on his back. Speaking of her memories of the sellers in her film American Honey (2016), Arnold goes back to childhood memories of seeing them in a parking lot or on the stairs of a building; the fragility of them trying to attract people’s attention, their solitary outside of houses where they were not welcome and on an asphalt road were touching memories. She tried to bring these people from her childhood and the feelings they gave her into her film. Although her starting point is usually an image from childhood, she is sometimes influenced by an image she encounters in adulthood. Sometimes, a woman trying to rush her children to catch a train in the snow, her clothes inappropriate to the weather, and even her sweatpants slipping off her waist while holding her children’s hands can be the starting image. She starts to imagine the woman’s life and the house she lives in through this image, and this image grows into a story. This was the first question she was asked at the Cannes press conference of her latest film Bird (2024). Although she normally wants her audience to guess the opening image of the film like a riddle, Bird says that the opening image of her film is a man standing naked on a roof. She wonders why this man, surrounded by fog, is standing there alone and naked, and tells the story of that man through the partially imagined and partially real eyes of a child who sees that man from the window in the makeshift corner of a room in her house.

Television

Andrea, like almost all children growing up on their own, spent their early years in front of the TV. However, since spending quality time with children was not yet popular in those years, growing up with a TV was not a situation specific to families in poverty. Andrea, too, as an enthusiastic viewer of American films and programs, realized at an early age the gap between the life she lived and the life she saw on screen. Those who compare her to the famous director Haneke find the most in common with the TVs that are constantly running in the background in her films. However, the purposes for which the two directors use television are very different from each other. While Haneke criticizes middle class families with indifferent approach to the violence and injustice that are sweeping the world in these scenes, Andrea Arnold uses a natural reflection of people who have become accustomed to the gap between the world they live in and the world they watch, who have forgotten their misery by imitating celebrities in her films – there are no harsh criticisms and questions, she just says “this is what happened and now you are looking at it”. Her Oscar-winning short film Wasp (2023) draws the real but sad portrait of a mother who compares herself to Victoria Beckham and her childhood sweetheart to David Beckham, and who cannot give her child anything to eat except granulated sugar while dreaming these fantasies. Similarly, in Fish Tank (2009), she presents the ridiculous daytime programs on the television that is constantly on in a miserable house, and the clips of rappers living their rich lives on their yachts. In Bird (2024), the television is played with song clips accompanying a childhood drama experienced in Bailey’s poor house, and sometimes with young people who are still in their teens. It is a background accompaniment where we watch frog videos that adorn the father’s dreams of getting rich. Television does not represent the middle class that turns its back on harsh realities, but the escape points where homes that live harsh realities get away from reality. For Andrea Arnold, who started her career in television, television is much more than just a household item.

Windows

Another common element Andrea Arnold uses in her films is the outside viewed from behind a glass. Usually, through the perspectives of the characters watching their alienated lives from behind a window, the director also perfectly reflects the social environment they are surrounded by. Perfection is not the perfection of the exterior spaces or the neighborhood, but the reflection. The cold neighborhood consisting of houses that bleed the eye with their poverty, the troublesome people who would make us cross the street with the distrust we would feel if we met them in normal life, and the passage to the sky where birds fly freely despite all this, are these windows through which the main characters watch the outside world. Sometimes the door that opens to the outside world from where they live, sometimes a peephole through which they observe the neighborhood, I wonder what goes through the minds of the characters as they look outside. The tension between the inside and the outside reflects the inner tensions of the characters onto the screen through the windows. A hand touching the glass in between, a bee hitting that glass and dying, a butterfly on the edge of the window emphasize the border. The representation of the border between dualities such as reality and fantasy, inside and outside, desired life and real life… in the movies is a transparent but solid glass. While the window that usually troubled young people stand in front of is shown in the skyscraper glass in the movie Red Road, we can perhaps accept the security camera screens that the main character is constantly in front of at night as a similar passage.

Film critics take a different perspective on Arnold’s windows:

‘For Arnold’s human subjects, windows and doorways function as cinema screens, and by watching the watcher Arnold asks us to similarly make cinemas of our worlds. As Amber Jacobs puts it, Arnold’s film operate on ‘a tactile, phenomenological level’ to produce and embodied alignment between the projected subject and the viewing subject’ Similarly, for Jonathan Murray: ‘audiences simultaneously look with and at the protagonists whose stories are being told’

New Realism, Contemporary British Cinema , David Forrest, Traditions in World Cinema, 2020, Page 83

Although this relationship between the viewer and the film may be difficult to understand with a phenomenological explanation (the end of the thread goes back to Heidegger’s Dasein), I can easily establish this relation with my own childhood, with my memories of the images of my old neighborhood that I watched from the window of my house. The distance between me and the child in my memories is both light years away and at the same time closer than I have ever been to anyone, and just like the windows in the film, what I look at from afar but know without being able to touch is my own world. This world that reaches out from the boundaries of the film is another strength of Arnold’s realism.

Motion, Rhythm and Dance

Another thing we often encounter in Arnold’s films is dance. Especially in scenes where there is no dialogue, emotions are conveyed to the audience through dance. The mother’s dance with her children in Wasp, Mia’s dance in Fish Tank, the emotional dance she does with her mother and sister in the final, the dances in American Honey, the father’s dance in Bird, the group dance scene at the end of the film and in countless other scenes, Arnold tells many things that cannot be expressed in words through the dance of his characters. For Arnold, dance is an impressive tool for emotional expression with its impulsive and raw nature. Like windows that serve as a passage between the characters’ inner and outer worlds, they release many emotions that are trapped, restricted and compressed inside them, not with words but with music, rhythm and movements that are in harmony with them.

While we are on the subject of motion and rhythm, we should also talk a little about the general motion in Arnold’s films. You may have noticed in his films that we often walk behind the hero, on her right or left, constantly with her. Sometimes we get on a bus or a car and watch the world in motion through the window. In fact, it is not the world that moves, but us, but where we are going is so unimportant that sometimes we feel like we are not going anywhere but drifting in the middle of nowhere where we stand. This constant state of motion becomes a situation that integrates us with the character and the character with the world. This sense of movement given by the shots with Steadicam and handheld cameras is also interpreted as a rebellion against the Thatcher era, just like the Punk movement. We watch Mia walking in 88 out of 886 shots in Fish Tank. Another feature of these shots is that they are continuous and uninterrupted, in other words, single shots, which increases the effect of the average duration of these scenes, which is 7.8 seconds. (Source New Realism, David Forrest, Page 106) David Rolinson interprets this effect as a criticism of the ‘Individual Participation’ rhetoric of the Thatcher propaganda of the period. It would be useful to elaborate on the rhetoric in question. I knew that Margaret Thatcher, whom I knew as the Iron Lady, earned this nickname as a result of a series of economic decisions that seriously oppressed the working class, but I had to read a little for the neoliberal interpretation of the Individual Participation mentioned. The idea that people should take individual responsibility to minimize their dependence on social support institutions and the state is based on the idea that individuals are responsible for the difficult economic conditions that the United Kingdom fell into, especially after the war. It is interesting that she does not ignore families when she says ‘There is no such thing as society, there are individual men and women and there are families’. Continuous privatization and the market economy also appear in Arnold films as abandoned factories, vacant lots, car dumps, polluted canal waters, etc. It is possible to come across these concepts and these places, which are not so foreign to us, in the outer skirts of big cities.

Political Perspective

Are this family on the poverty line and this child growing up without attention a family and a child as I know them? In other words: What exactly makes a family a family and a child a child?

When it comes to social realism, a political perspective is essential. At this point, the political perspective in Andrea Arnold’s films is interpreted in three different ways. A group of film critics criticize her for being apolitical or for not reflecting the class differences experienced by the segment she covers in her films ‘realistically’ enough. Her stories that shed light on the inner worlds of the characters and their relationships with the smallest details in their environment, the ordinariness of the reflection of even the most dramatic situations with an everyday simplicity; in short, the perspective that examines the characters ‘individually’ does not seem to have the broad plan required for social realism. It is said that the liberation in the analysis section of Arnold’s films denies the collective experience and that class analysis lacks depth. Another group (as in the Thatcher comment) can politicize her films more than they are by over-analyzing them. The dance scenes he constantly uses in his films, the scenes of the characters in motion are analyzed in the finest detail and transformed into a subtext criticizing political propaganda. Of course, Arnold does not have any comments supporting these views. Since he does not read the analyses written about his films, he does not comment on them. Ignoring this situation, the third and last group we will look at draws attention to his innovative approach to the field of social realism. ‘Arnold’s films occupy a new political terrain. Her candid, senroy mode of depicting the extremity of sexual/maternal ebodiment transmits and implants into the viewer not a social (moral) message but, instead a new mode of ethical and ontological relatedness’ (Amber Jacobs, 2016) Although the innovation Jacobs mentioned is prominent in the characters in Milk and Red Road, Arnold’s new, fresh and different perspective on social realism is not limited to this. Her provocative approach to sociological and cultural norms is very clearly seen in her films, and this clear view stems from her ability to make the audience see the world through her eyes. Yes, Arnold turns her audience’s head in that direction, but what they feel and interpret when they look are completely specific to their audience. One of the characteristics of the cinema called New Realism is that it has a perspective that the audience reaches spontaneously through the lens it holds over individuals and individual characters. I agree with the view that this approach is more effective than the old/classic social realism, especially on audiences living in today’s stimulating chaos.

I did not know before that Arnold also shot an advertisement for a campaign for young people in need of support, in addition to her films. Previously known as the Prince’s Trust, with its updated name, the King’s Trust shot an advertisement for a campaign launched to meet the education, course and job needs of young people between the ages of 11-30. The commercial called Youth can do it was a means for Arnold to reach out to the young people in the slums she featured in her films. Thus, she established her first connection with royalty, and who knows if she will receive a royal title in the future due to her success in cinema?

Liberation

Although the main story in Andrea Arnold’s films is very different from each other, there is a small but great liberation in almost all of them. The release of a bee trapped by a window in Wasp, the liberation effort of the stubborn Mia who dares to face unimaginable dangers in order to free a chained horse in Fish Tank, Mia’s journey to freedom in the finale of the film, the bond the girl establishes with the dog in the short film Dog, the relationship the girl establishes with the Bird character, a seagull in human form, in the film Bird, Jackie’s liberation from hatred, regret and isolation in the finale of Red Road… In almost every film, we witness the moment of liberation or the effort of liberation of the character who struggles to escape from the internal and external entrapment she is in. Sometimes this is an animal that the main character has a bond with, and sometimes it is the character herself.

Characters

The characters that directors create are of great importance in their success. Especially if these characters are used as templates even years after them and other characters are created on them, we can definitely talk about a success here. Andrea Arnold is also a director who guides those who come after her with her characters. When I started watching Marcella (2016), I had not yet watched Andrea Arnold’s Red Road (2006). But Marcella really caught my attention. When I saw all the features that we are used to seeing in male heroes in noir films, such as her clothing, walk, demeanor and attitude, in a female character, everything seemed to be a whole, even though she was an outsider. An introverted darkness, an obsessive ruined character, like what Michael Mann described as outsiders, she has nothing to lose and that is where she gets her impressiveness from. Killing Eve (2018) came next. Although we cannot talk about a character who has absolutely nothing to lose there, the demeanor, attitude and obsessive state of mind were similar. A character who would sacrifice everything she has for the sake of her obsession. I discovered the origins of these two characters when I watched Andrea Arnold’s Red Road. Three women who are so similar in their clothes and attitudes. Three women who dress the same way, from their furry anoraks to their ringed hobo bags, and who are obsessed with catching criminals beyond the law.

The Red Road film has an interesting shooting story as Andrea Arnold’s first feature film. In 2003, Lars von Trier‘s production company Zentropa collaborated with Scottish Sigma Films to establish Advance Party. Advance Party is a trilogy game with rules. 3 films, 3 new directors, the directors’ first feature films, each film must take place in Glasgow, and the same 8 characters must play in all films (those who have heard of Dogme 95 know that this is not Trier’s first play). After the rules are set, Danish Lone Scherfig and Anders Thomas Jensen list the 8 characters with short explanations. The three selected directors Andrea Arnold, Morag McKinnon and Mikkel Norgaard will direct their films as they wish, in accordance with these rules. Andrea Arnold’s first film Red Road is a great success. Morag Mackinnon’s film Donkey (2010) experiences various misfortunes. They give up on including an actor (Andy Armour) in the film. The 75-year-old actor is physically unwell. Andy Armour is very disappointed when he is removed from the film. He tells the Scottish newspapers, “They have gone back on their word, that promise is broken and I’m broken.” After saying this, he learns that he has cancer and dies a few months later. The film is cursed because it breaks the rules. After the entire film crew caught a virus during the shooting, the weather conditions, the editing, and all sorts of bad luck on the set, the film sold 200 tickets in its first weekend of release. It is said that this box office figure, which happened without any advertising, is good. I don’t know. Mikkel Norgaard, the third director of the Trilogy, disappeared (gave up) and the third film was never shot. In short, Andrea Arnold is the winner of the Advance Party. Despite all the restrictions regarding the characters, location and actors, she has put a film out there with her own rules.

Even in her limited character selection in her first feature film, Arnold, who made her own touches felt, deals with the end of childhood and the limbo of transition to adulthood in scenarios where she is free. Like the turning of seasons, the turning of human periods are also memorable when surprising changes occur rapidly. In Arnold’s films, the stories of adults who fail to become adults and children who cannot become children draw attention. These characters are usually shaped in the shadow of women who became mothers at a young age and were forced to become adults too early to experience their own youth. We see that these mothers, who even put the basic needs of their children to the back, create “children who have not experienced childhood”. Although mother-child relationships, siblings, childhood friendships and mothers’ lovers are prominent in Arnold’s cinema, none of these bonds are normative in the sense we know them. Although there is a sense of longing for the traditional family structure in her films, the reality experienced by the characters is much more complex and different. The director’s latest film Bird adds a new element to this range of relationships: the father figure. However, this is also quite far from a classical father portrait, and as always, it carries a depth that turns the norms upside down. In this sense, the characters reveal the fragility and complexity of not only individuals but also relationships. Her cinema can be defined as narrating both growing up and not growing up.

At this point, it is also noteworthy that the director approaches motherhood from very different perspectives with the mother characters. I can personally count the short film Milk (1998) as one of the bravest films I have ever watched. I remember being in awe for a while after watching this magnificent work, which is about a mother who does not experience her mourning in the way her environment is accustomed to after losing her baby, and even though years have passed, I still remember many scenes like the day I first watched them. Hetty, who breastfeeds a street thug she does not know with the milk flowing from her breast and later attends the funeral of her baby with her husband, is one of the most extraordinary characters presented on motherhood, loss and mourning. In the film Red Road, she similarly added motherhood, loss and law, and the feeling of revenge, and showed her mastery in creating titillating combinations by associating all these situations with sexuality.

The change that Arnold has shown in terms of characters over the years is noticeable in the movie Bird. The distance she kept towards adults who did not show love and attention to their children in many of his previous movies decreases in this movie. Whether it is because of the years that have passed or because Andrea Arnold has started to forgive her parents even though she does not fully understand them; a forgiveness is observed towards the immature father in the movie. In the scene where the father says to his son “I have never regretted to have you” and then starts listening to the dad song, Arnold’s empathy towards immature parents is remarkable. In fact, the acceptance in the three-way dance in the finale of Fish Tank is replaced by the forgiveness between the father and his two children during a scooter ride 15 years later in the movie Bird. I guess the order is as follows: first acceptance, then forgiveness.

Yes, after listing all these common components, I can now move on to the definition of Andrea Arnold’s cinema, one of the most powerful directors of the new realist approach. First of all, it would be appropriate to start with the narrative language shaped by social realism and transcending that reality. Arnold’s cinematic language brings what is outside to the inside by settling in the streets, backstreets, and abandoned plots of land in her films. While this is in a sense the relationship of the characters looking out the window with the outside, it is also our relationship as the audience with the characters and their world. While the director makes even the most ordinary detail of that world visible in an impressive way, everything, all these ordinary things turn into a story that complements each other, and more importantly, into a flawless atmosphere that surrounds the audience. Arnold presents her characters without squeezing them into their classes and social contexts, remaining loyal to the emotional and individual worlds of each of them, and provides her cinema with not only a reflection of reality, but also a human state lost in that reality. Dreams, disappointments, and the desire to survive, like every person thrown into the world, make us feel the struggle for existence to our core. Along with it, we also question the characters, the social structure and even the way we perceive the world. From the gap between hunger and fantasies in Wasp to the strange mixture of mourning and sexuality in Milk, to the rebellion of youth in Fish Tank and Bird, each character makes their voices heard in their own class and cultural context. Therefore, I can say that Andrea Arnold, one of the most powerful directors of the neo-realist approach, draws her power from the fact that she can be so impressive while presenting the inner worlds of her characters, the places they are surrounded by, nature and the relationships between each of them as they are. Starting with the guiding image, the journey she invites her audience to, intertwined with the world, is filled not with messages about reality, but mostly with the feelings evoked by the images. It is provocative, unpredictable and exciting. As the years pass, sometimes a fairy tale may come across us on this path, heartbreaks may turn into understanding and acceptance; I may say we have grown up now or returned to childhood for a while, at the same time.

Zeynep Bakanoğlu