The Past is Never Dead. It’s not Even Past.

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

William Faulkner’s quote serves as a good introduction to Nickel Boys. Even if buried in an unmarked grave, there is a past that never dies and will never be forgotten, no matter how many years pass. Racism in American history is like bile rising to the mouth; bitter and burning the throat.

That was a heavy start. So let’s take a pause and lighten up with what POV (Point of View) shots remind us of. Recently, we’ve frequently seen POV shots in cat videos on social media. Thanks to a camera strapped to the neck of a huffing and puffing cat, we run alongside it, brawl with stray cats, climb walls, and leap from trees. For a few minutes, it’s fun to see what that sweet little furball troublemaker is up to. Naturally, this technique isn’t considered very ‘artistic’. While it has been attempted in other films, it remains an uncommon method.

However, in RaMell Ross’s adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s 2018 novel The Nickel Boys, POV is used in entirely different ways. When the POV shot starts from a fixed point with minimal movement, it aligns with the hazy, slippery nature of childhood memories.

As the film progresses, it becomes apparent that the cinematography is also used as a tool for creating mystery like a foreign presence inhabiting someone’s body. We see what he sees, hear what he hears.

The Black child we embody says:

“My name is Elwood.

What do I look like?

Am I frail, tall, short?

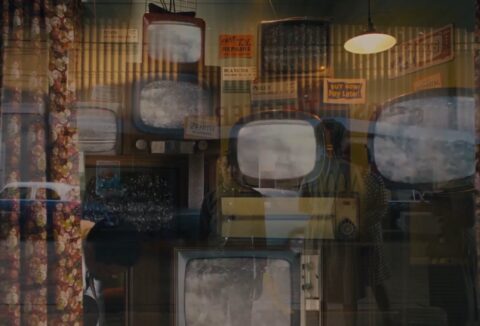

In the reflection of the shop window I stood before, I saw my height.

When I fell in the park, I saw how I cried.”

This sense of being a stranger in another body gains more meaning as the film reaches its resolution, making us recall it once again.

The movie can be divided into three sections: introduction, development, and conclusion. Its nonlinear editing stitches these segments together in fragments, ultimately forming a cohesive whole.

The introduction introduces us to the main character, Elwood, while also depicting the racist atmosphere of the time without resorting to slogans. We’ve likely seen similar portrayals countless times, yet stepping into this body makes us feel fear and entrapment. Fear and anxiety; perhaps the strongest emotions here.

The second segment unfolds in a reformatory, the inevitable result of a series of unfortunate events. For the first time, a second perspective is introduced: Turner. In the cafeteria scene where Elwood meets Turner, we experience the same scene again, this time through Turner’s eyes. From his perspective, Elwood appears insecure, afraid – no, afraid is an inadequate expression- terrified young man. This section also subtly plants clues for the film’s final twist.

The third part begins from behind the shoulder of a man looking at a computer screen years later. As he browses old photographs and documents, it’s clear he’s chasing the past. Is he the adult Elwood? It is hard to tell. His name appears in a few documents, so it must be him. If he’s left his dark days behind, we can continue watching the film in peace. Or can we?

While I found the first and second segments strong, the third one felt like watching a computer game, which I didn’t particularly enjoy. The shift from a first-person perspective to an over-the-shoulder shot reminded me of an East Asian belief that spirits of the dead cling to the shoulders of the living until they, too, pass away. When Elwood dies, the camera exits Turner’s perspective and moves behind him—a distinctly noticeable transition.

In the final scene, we are met with an image similar to Elwood’s childhood memory from the beginning. The resemblance between the two moments—the start and end of a life—is profoundly moving.

We had captured a similar one in childhood and adulthood memories with these two, exquisite twin shots

When we see at the end that Elwood has died and Turner has taken his place, the initial feeling of being a stranger in someone else’s body actually belongs to Turner’s character in the film, making the identification between the viewer and Turner even more pronounced.

If I start with the aspects of the film I liked the most, I must say that, in terms of cinematography, it is definitely innovative. The connection between the viewer and Turner’s character is cleverly constructed. The editing work, in particular, is extraordinary. It is clear that a lot of effort was put into the hybrid structure of the film, which leans towards a documentary style. Additionally, the fleeting glances, inserted images, and sounds in scenes involving physical and sexual violence were quite striking. The music, too (jazz) was very well in sync with the rhythm of the film.

Considering its nominations at the 97th Academy Awards, I believe that instead of Best Adapted Screenplay, it should have been nominated for Best Film Editing. Nicholas Monsour was, in my opinion, the most outstanding contributor to the film.

After listing what I liked, I can move on to what I didn’t. Were these highly ‘technical’ choices, especially the over-the-shoulder shots in the third part, exhausting for the viewer? I think so. While it has been widely discussed among film critics, festival circles, and cinema professionals, it is not a film that would reach a broad audience. Of course, it doesn’t have to be, but I personally find independent and innovative approaches most valuable when they are free artistic expressions. Nickel Boys, however, gave me the impression of being an overly calculated production aimed specifically at a certain audience (film critics, festival circles, etc.), which made it less exciting for me.

Furthermore, although I mentioned that the story is not overly sloganized, it is hard to ignore that the film almost demonizes the white children at the reformatory within its Black-and-white struggle. Yet, the real-life Dozier School (Florida School for Boys), which operated for more than a century and serves as the film’s basis, was a place of torture for white children as well as Black children. While sexual violence is depicted only through a mixed-race Hispanic child in the film, a 2013 investigation into the school revealed through remains and witness statements that the so-called ‘White House’ ,the section for white boys, was not just a place where they played football and were set up to win rigged boxing matches.

Therefore, the absence of terrifying Ku Klux Klan hooks hanging from trees for the white boys does not mean they were not subjected to abuse in that school. Whether this one-sided narrative exists in the original source material is unclear without reading the book, but it can be seen as a perspective that weakens the film’s storytelling power.

The film deserves recognition for its bold technical choices and powerful execution. While I wouldn’t consider it a masterpiece, I believe that, given its subject matter and the attention it has drawn from film professionals, it will continue to be discussed for a long time.